Marine Corps University Communications Style Guide

CHAPTER FIVE: THE RESEARCH PROCESS

Research is fundamentally a problem-solving exercise. It is a search for evidence that will help you investigate and answer a research question in the way that best suits your particular context and purpose. You participate in research processes every day. When you need to decide what kind of car or computer to buy, for example, you typically conduct research—by talking to others or by searching online—to inform your decision. When you need to know whether a particular food has health benefits or dangers, for example, you conduct research to find the answer. Decisions on the battlefield are also the result of an effective research process. While the tools you use to conduct that research may be different and the stakes are higher, the process you use to examine your assumptions, revise those assumptions, and come to a conclusion is largely the same. While a student, you collect information by searching databases, reading books, and interviewing subject matter experts. In the operating forces, this information might come in the form of reconnaissance, after action reports, and field observations. A skilled commander knows how to organize this information, make sense of it, and come to a conclusion, even as the situation continues to evolve. Similarly, when you approach research as a student, you will find that your conclusions will change as the information you collect challenges the assumptions on which those initial conclusions are based. Just as you would adjust your battle plan in reaction to developing intelligence reports, you will fine-tune your argument based on the new information you collect throughout the research process. Research, therefore, is not merely an academic exercise. The ability to sort through information, isolate facts from unfounded assumptions, and come to a decision, even when the situation is constantly evolving, is an invaluable skillset for a successful military leader. This chapter provides strategies for building those essential research skills and includes: an overview of the research process; finding a topic and collecting background information; primary, secondary, and tertiary sources; and working with sources.

CSG 5.1 Overview of the Research Process

When you undertake a writing project that requires research, your goal is to find information, evidence, and resources that will broaden your own understanding of a subject and its context so you can gain perspective, reach insights, and ultimately solve a problem. The process of conducting research helps you to develop expertise about a subject, issue, or event. Writing about this research allows you to organize your ideas into a logical presentation or argument that your readers can follow and act on.

As a process, research is messy. You might begin with a single question and find that in order to answer that single question, you must answer many other questions first. Research can be time consuming. Many researchers do not mind investing many hours into their research, however, because they are passionate about their topics. Prepare to spend a lot of time researching your topic when you undertake a research paper.

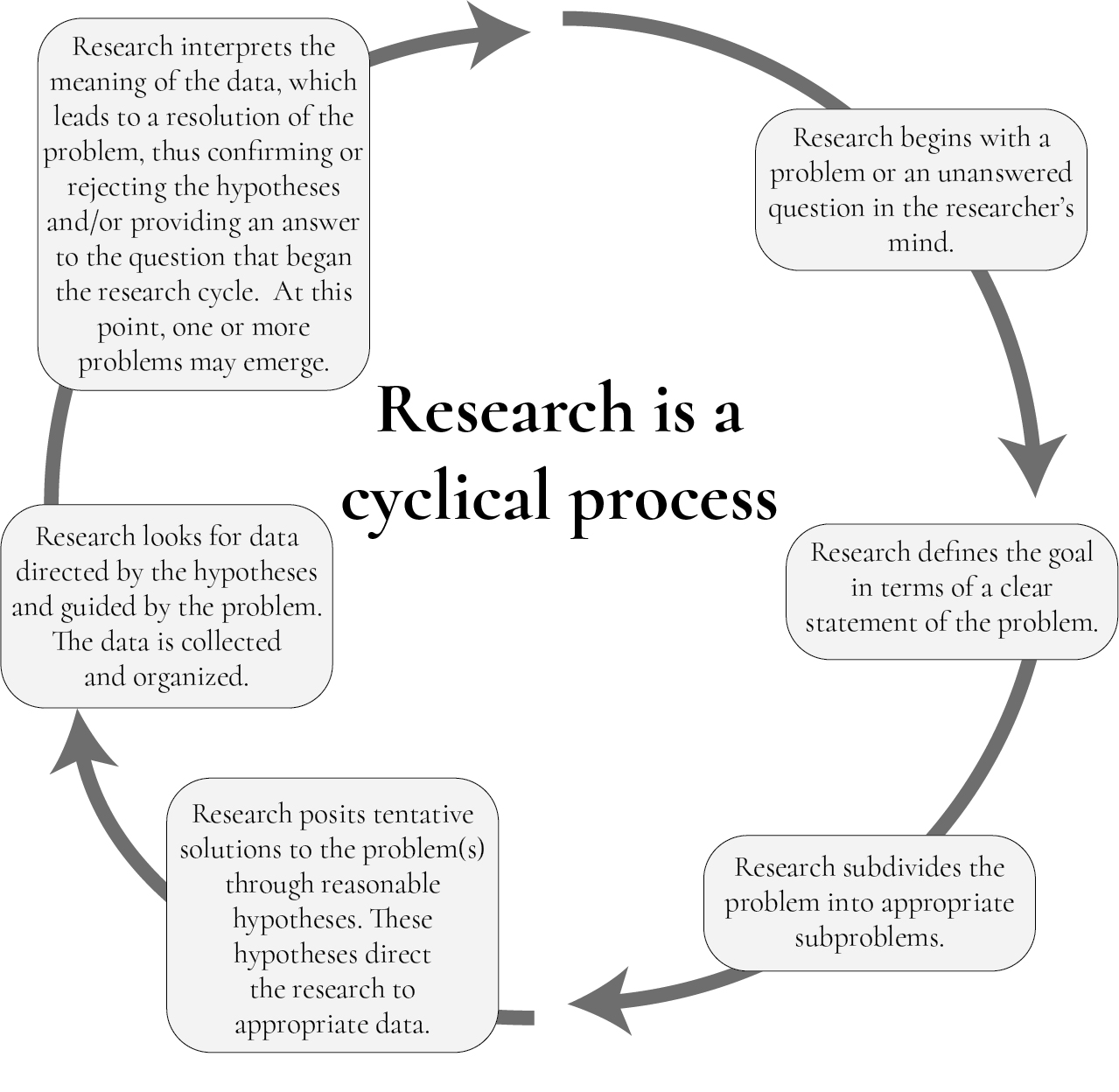

As an MCU student, you have access to a team of reference librarians to support you throughout the research process. You will find the research librarians in room 121 of the Gray Research Center, or you can access them online. The research process is both cyclical and recursive, as figure 27 illustrates.

Figure 27. The research process

Source: adapted from Paul D. Leedy and Jeanne E. Ormrod, Practical Research: Planning and Design, 8th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, 2005), 7.

Research typically begins with a problem, a question, or even a writer’s simple curiosity about something. As you investigate the problem, you begin to articulate a research question (or a problem statement). The information you uncover leads you to articulate several additional questions or subproblems related to your research question. As you conduct research, you develop and adopt (or discard) hypotheses to help you answer your questions. You collect and organize information that supports or refutes your hypotheses, and then you go through the cycle again: You rearticulate your research problem, restate your goal, reexamine your subproblems, reposit solutions, revise your hypotheses, and reorganize your data. At some point, you draft a paper that presents your argument to specific readers who can act on your research. You can find more information about developing a research question and constructing an argument in chapters 6 and 7.

Research Is a Process: Your Initial Hypothesis Can and Should Shift

If you are writing about a problem or issue that is familiar to you, you likely have a sense of what the answer to your research question might be. In fact, you might be tempted to jump directly into writing a thesis statement and collecting evidence to support that thesis. The research process, however, is not an exercise in proving your initial hypothesis. It should be a process of exploration and one that gives you the opportunity to challenge some of the beliefs you already have about a particular problem. Sometimes this process may lead to an affirmation of previously held beliefs, but it should allow for examination of other points of view.

When Should I Stop Researching?

The point at which the research process ends and writing begins is not clear-cut. In fact, many researchers find it helpful to complete some preliminary writing before conducting research. This may mean making a list of elements you find interesting about your topic, drafting a research question or hypothesis, or even freewriting. If you are undertaking a major research project, such as an MMS, future war, or IRP paper, you will notice you may move back and forth between the research and writing processes as you compose your paper. For instance, you may sit down to write only to realize your thesis has shifted and you now need more evidence to support your specific claim. Similarly, you may feel overwhelmed by your sources and all of the subtopics that are inherent in your main topic. In this case, you may need to do some outlining or mind mapping to determine which aspect of your paper you are most interested in presenting. Once you have sufficiently narrowed your focus, you can proceed with your research in a more focused manner. For more information about mind mapping, outlining, freewriting, and other types of invention strategies that may help you to develop ideas about your topic, refer to chapter 2. Deciding when to stop researching and write your paper can be difficult. When writing about current topics such as North Korean nuclear proliferation or the COVID-19 pandemic, you will likely find new information that may change your perspective daily. It is important to remember that your research paper represents a snapshot in time, a jumping off point for future researchers to continue the conversation surrounding your topic. Your research paper should demonstrate that you consulted the existing literature on your research topic that was available at the time period in which you were writing.

CSG 5.2 Finding a Topic and Collecting Background Information

As you look for an area of research to meet the goals of your project or your writing task, you will begin by searching for background information on topics you find interesting. The goal of your background research should be to familiarize yourself with definitions and general issues associated with a subject that interests you.

While choosing a topic can be one of the most difficult aspects of writing an academic research paper, it can be rewarding, particularly when it allows you to satisfy your curiosity about something or when it becomes an opportunity for professional development. As you begin brainstorming, you may want to think about your experience. Is there anything you would do to change your organization’s technology, strategy, or training? Were there any specific problems or issues you encountered that you would like to find solutions for? Often, the most fulfilling research projects are those that have relevant real-world applications.

Where to look for topics:

1. MCU’s military-specific research guides: these guides are curated specifically by MCU reference librarians. Topics are updated every one to three years and are available on the GRC website. The reference librarians have also compiled a variety of resources and articles on the library’s academic support pages.

2. MCU course material: as you complete your assigned readings, keep track of the problems, themes, and ideas you might like to investigate further. Keep in mind that your research topic does not need to be obscure, and some of the best papers find new ways of looking at old problems (e.g., using Clausewitz’s trinity to understand how to address a modern crisis in Venezuela). As such, there are a wealth of potential research topics to be found in your regular course material.

3. Articles published by other PME institutions: publications from the wider PME community are another window into current issues in national defense. Consider skimming strategic planning journals such as Parameters, Small Wars Journal, the Journal of Advanced Military Studies, or Joint Force Quarterly to familiarize yourself with some of the debates and critical perspectives in military studies. Reading these types of publications will also give you a sense of what a well-written research paper looks like. Researchers will often propose issues for further consideration or ideas for future research in the conclusion of an article. These conclusions and recommendations may provide a point of departure for your own research. In addition to reading research-based articles, watching or reading the news can offer ideas for further research. Once you start looking for research problems, you are likely to find them nearly everywhere.

GRC reference librarians: If you are feeling overwhelmed at any stage of the research process, you can always reach out to the GRC reference librarians, who have a wealth of knowledge about the topics students have researched in the past, the sources students have used in their writing, and the information available on certain topics. Before you commit to a topic, you should ask yourself the following three questions:

• Am I interested enough in this topic to commit myself to hours of research and writing on it?

• Is this topic appropriate for my writing assignment (or for another writing goal, such as a publication)?

• Can I find credible primary and secondary sources about this topic?

If you can answer these questions in the affirmative, you are ready to perform a background investigation of the topic. Keep in mind, though, your topic is not the same as your central research question. Your topic is a general area that you will become more knowledgeable about so you can articulate a specific research question to investigate and write about. The answer to your central research question will become a working thesis statement. Before you can develop that thesis statement, though, you must gather background information from both primary and secondary sources.

CSG 5.3 Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Sources

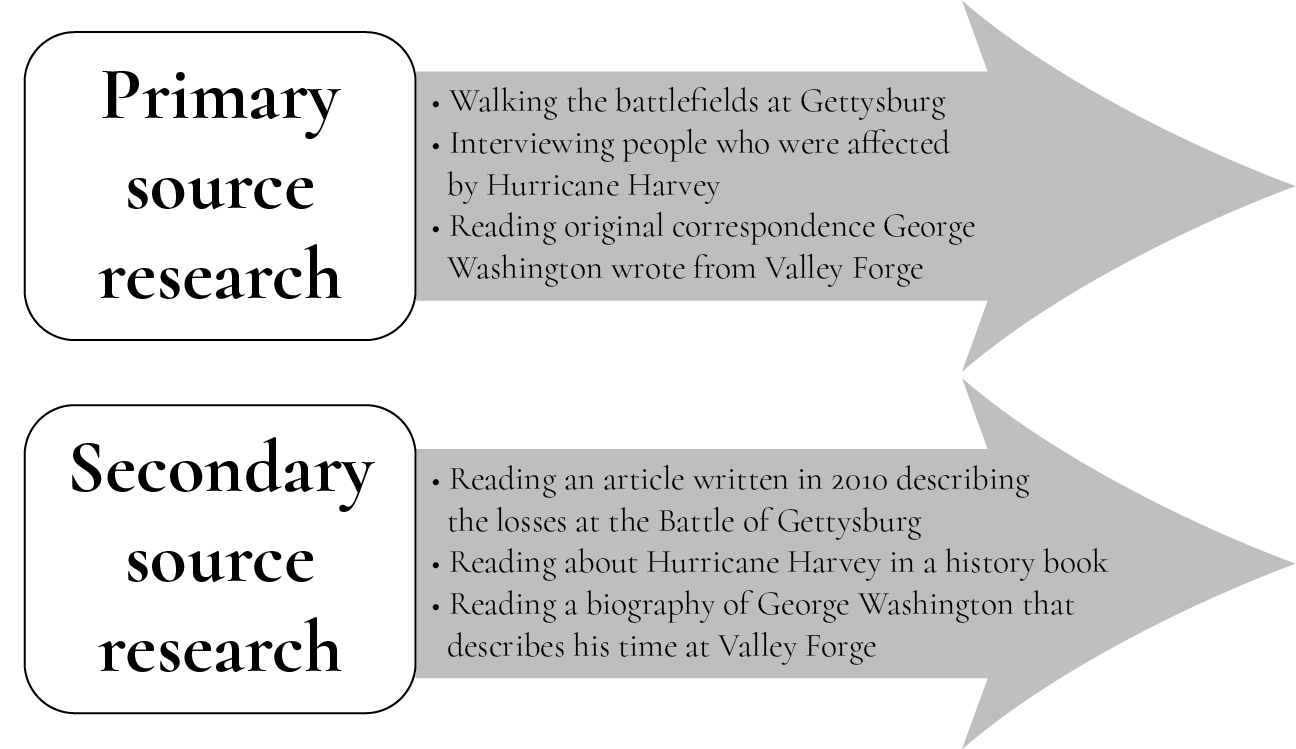

As you conduct your research, you will likely consult a variety of primary, secondary, and tertiary sources. Primary sources are original sources of information, such as original archival documents or artifacts. Secondary sources comment on primary sources—that is, they are interpretations of primary sources, such as critical reviews, journal articles, and dissertations. Most reference materials are considered tertiary sources, which include dictionaries, encyclopedias, and textbooks. Researchers will often consult tertiary sources first to gain background information. Then, they will move on to secondary sources to get a sense of the main critical debates in the field. Finally, they might consult primary sources to develop their own stance on the debates they find in tertiary and secondary sources. In other words, researchers tend to start with sources that are further from the original source and then move to more specific types of information, such as artifacts or archival documents.

CSG 5.3.1 Tertiary Sources

Tertiary sources may combine information from both primary and secondary sources and include reference materials, such as dictionaries, encyclopedias, and handbooks. It is typical to consult tertiary sources to gather some background information or general knowledge on a topic before you begin conducting more focused research.

CSG 5.3.2 Secondary Sources

Secondary sources are the resources we often think of first when we think about writing a research paper. They are the published resources that comment on or analyze primary sources as well as other secondary sources. Secondary sources can help readers make connections between ideas or raise questions about issues and perspectives. Additionally, secondary sources advance disciplinary understanding and create new theoretical frameworks that readers use to attain insight. Secondary sources have been vetted by publishers and expert reviewers who have agreed that the information in a secondary source is important and that it represents a current view of a subject. It is important to differentiate between credible secondary sources and those that are questionable; for example, nearly anyone can edit or add content to a Wikipedia page, so you may not want to consult Wikipedia when providing evidence to support your claims. While secondary sources can provide useful and reliable information, this data has already been analyzed and filtered for you by the author. This means the work is subject to the secondary source author’s personal biases or interpretation, as well as the ways in which the author views the field or the discipline.

Although it is important to read critically to be aware of the biases and inconsistencies that may be present in secondary sources, these sources are an essential component to include in your research. By reviewing secondary sources, you will familiarize yourself with some of the main arguments and critical perspectives on your topic. For more information about evaluating sources to determine bias and credibility, refer to section 6.3.

When building an argument, it is especially important to use secondary sources as a foundation. For instance, if you are writing a paper that proposes a new operational culture perspective for Africa Command (AFRICOM), you need to briefly discuss some of the main operational culture perspectives that already exist. You may want to synthesize what you view as the strengths and weaknesses of these multiple perspectives to create your own model. Then you will use primary sources—reports from the field and interviews with African culture experts, for example—to show why your model would be effective.

CSG 5.3.3 Primary Sources

Primary sources are original sources of information. In historical, military, and professional research, these primary sources of information typically include archival documents such as letters, diaries, legislative bills, laboratory studies, corporate reports, field research reports, operational orders, after action reports, command chronologies, command memoranda, military orders, message traffic, unit diaries, map overlays, and eyewitness accounts. Primary sources include information researchers gather for themselves by means of interviews, surveys, or observations.

When you are searching for background information on a topic, your primary sources might include the people you consult who work in the field or who have become experts on the topic. These sources can provide you with definitions and describe for you some of the current issues associated with your topic. They can give you their opinion about additional sources available on the topic. Once you have developed a strong command of the subject matter and you have articulated your central research question, you can return to your primary sources with more specific inquiries into your main idea.

For a research paper to be considered original research, it should include primary source material. Conducting primary research means going back to the original document, work of art, letter, or battlefield and making your own observations about that particular place, event, person, or object. Your central research question will drive the framework and structure of your investigation.

There are times when consulting a primary source is not feasible; for example, if you have three weeks to write a paper about the D-Day invasion, it is unlikely you will fly to France to study the beaches in person. However, you may be able to find valuable correspondence in the Marine Corps History Division Archives. When viewing primary sources, remember to place the object or document you are studying into its context; you can do this by studying the time period in which the source was written. Questions to ask include the following: How did the society, politics, and economics of the time period affect the object’s significance?

Figure 28 offers examples of primary and secondary source research.

Figure 28. Examples of primary and secondary research

Once you have collected your background information, you will develop an understanding of the issues and questions surrounding your research topic. From there, you can develop a working research question that will help direct further information-gathering.

CSG 5.4 Working with Sources: Reading Critically and Actively

Constructing a strong, well-reasoned paper is as much a thinking process as a composing process. Actively engaging printed sources and knowing how to read critically is an essential component of your writing process.

When you read critically, you attempt to not only understand another writer’s argument but also to think about what biases and underlying assumptions might inform that argument. You will also want to think about how the argument is constructed: What are the premises on which the author builds conclusions? How does the text relate to others you have read on the subject? Critical reading should prepare you to respond to what you have read—it is the first step in any type of analysis, synthesis, or evaluation (see chapter 2 for more information about analysis, synthesis, and evaluation).

While readers may have their preferred critical reading process that allows them to prepare to interact with a text, if you are not sure where to start, you might consider using some of the strategies below. You will notice that the proposed critical reading method requires you to read the text three times.

Critical Reading Strategies

1. Skim the text or preview the material.

2. Slow down and read the full text using active reading strategies. These include questioning the text, annotating the text, taking notes, and mind mapping.

3. Review the text and the areas you have highlighted and annotated as well as your own notes and mind maps. Consider the relationships among the key ideas. Look for main patterns, themes, or ideas throughout the text. Review the concepts you do not understand.

In the rest of this section, you will find descriptions of a few strategies that can help you read actively and critically. They include the following:

1. Previewing

2. Questioning

3. Annotating

4. Taking notes

5. Analyzing

6. Responding

7. Journaling

While you may not use every strategy each time you read, these approaches may help you to read more effectively so you can create new knowledge you can draw on as you write. Using active reading strategies helps you avoid having to go back to relearn concepts you have previously read about.

CSG 5.4.1 Previewing

Previewing refers to the process of skimming the chapter before you begin to read. When you preview material, you will want to look at the main headings and subheadings. What do the main topics tell you about the writer’s argument and organization? What are some of the main ideas? If you are reading a chapter in a textbook, what are some of the questions the author asks at the end of the chapter? You may want to look for the answers to these questions as you read. At this point, you may want to identify who the author is, what background or level of expertise he or she has regarding the topic, and what potential biases could be present based on this background knowledge and experience.

If you are previewing a longer text, such as an entire book, you may not want to skim the entire text. However, you will want to take a look at the table of contents and the preface. By looking at this introductory front matter, you will have some idea of the approach the book will take and the main analytical perspectives the author will incorporate or disprove throughout the book. The preface and table of contents will give you some insight into the author’s purpose, framework, and possible biases.

CSG 5.4.2 Questioning

Once you have previewed the text, you can begin using active reading strategies to interact with the text. It may be useful to think of every text as a conversation. If the author were presenting the text’s main argument with you over a cup of coffee, how would you respond? Would you agree with the author’s main argument? Would you present an alternative point of view? Are there parts of the argument you agree with? Are parts of the argument unsupported or questionable? Are there any terms, concepts, or models you do not understand? Are there perspectives the author may be missing? You will want to keep these questions in mind as you read.

CSG 5.4.3 Annotating

Annotating is the process of marking important ideas, definitions, and concepts in the text. When you annotate, you highlight key phrases, indicate supporting points you agree or disagree with, and even ask important questions in the margins. If you are reading a digital copy of a text, your e-reader will probably have an annotation function. If you are reading a hard copy text that does not belong to you, you can take pictures of important pages or visuals on your phone or use post-it notes to indicate key ideas. You can even color code the post-it notes to trace main themes throughout the reading. For instance, if you are trying to determine how the United States applied diplomatic, informational, military, and economic (DIME) principles in a particular conflict, you could assign a color to each element (e.g., yellow for diplomacy, green for information, red for military, and blue for economics). When you review the text before an exam or before sitting down to draft a paper, your post-it notes should lead you to the most important points. As many books, articles, and other documents are now available online, you also may annotate by copying and pasting a portion of the article and its reference information into a Microsoft Word document. This approach will allow you to highlight blocks of text and use track changes and comments to note your questions and/or thoughts in the margin.

CSG 5.4.4 Taking Notes

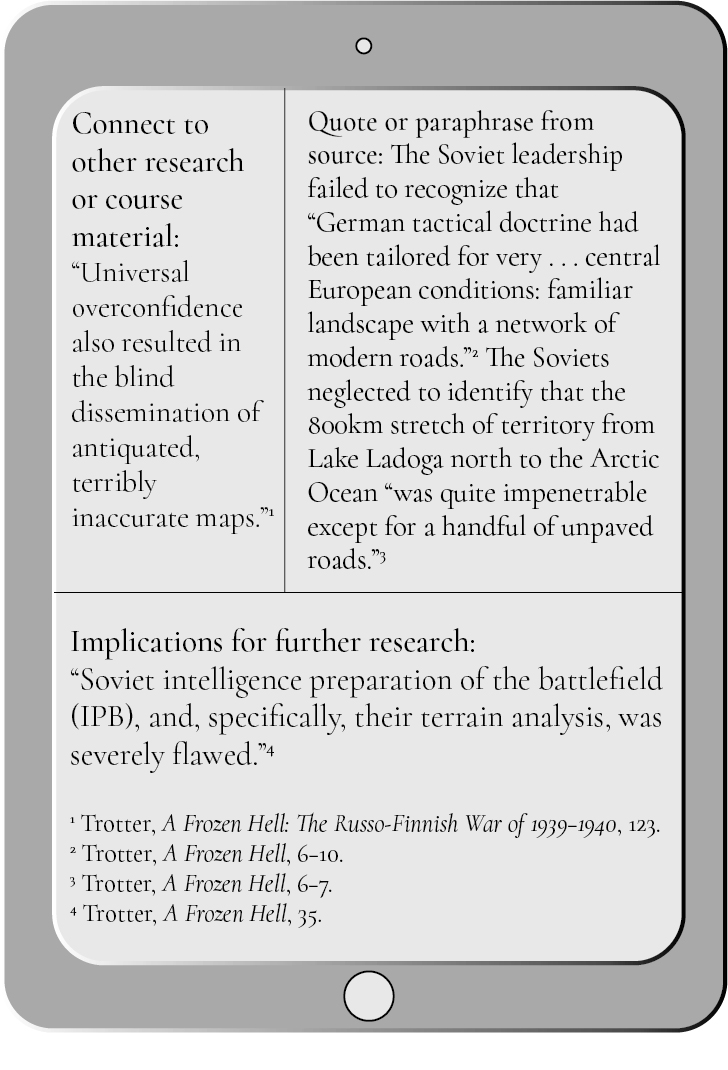

Many students prefer to take notes in addition to (or in place of) annotating. When you take notes, make sure you are not merely summarizing the material you read. Instead, focus on connecting the text to other material. Figure 29 displays an example of the Cornell Note Taking method, which may help you think about these connections as you write down important concepts or facts.

Figure 29. Cornell note-taking method

Source: concept developed by Walter Pauk, How to Study in College (Boston, MA: Houghton/Mifflin, 1962).

In the Cornell note-taking method, you divide your page or screen into three sections. In one section, you summarize or quote an idea from an outside source. In another section, you make a connection between the new idea and a previous idea you have learned in class or have read about. In the third section, you write about the implications of this idea: What does it mean in a particular context or for future study? This strategy is useful when reading about the central ideas of your research.

CSG 5.4.5 Analyzing

Regarding textual analysis, Mike Palmquist says in The Bedford Researcher, “Writers who use this form of analysis focus both on what is actually presented in the text and what is implied or conveyed ‘between the lines.’” You will ask yourself about the structure of the argument. You will want to examine the author’s assumptions, the sources and evidence he or she uses to support those assumptions, and possible author biases. Below are some questions you will want to ask yourself when you analyze a text.

1. Do you agree with the assumptions the author makes? Why or why not?

2. What type of evidence does the author use to support these assumptions (e.g., surveys, interviews, or field research)?

3. Does the author use secondary sources to support the argument? If so, are the secondary sources written by credible researchers?

a. In which publications do these sources appear?

b. Are these publications considered biased in any way?

4. What kind of logic does the author use to support the text’s main idea?

a. Does the author rely on emotional appeals?

b. Does the author include unsupported, sweeping generalizations?

5. Who is the author?

a. Does the author belong to an organization with known biases?

b. What are the author’s credentials?

6. What is the author’s purpose for writing?

After analyzing the arguments others have made, you can use rhetorical analysis to determine where your argument fits into the academic conversation. In this way, you can point out gaps in logic of existing arguments and emphasize the strengths of your own use of appeals. For more information on understanding the rhetorical situation, see section 2.1.

CSG 5.4.6 Responding

Generally, responding to a text involves taking a few minutes to write down your initial reaction to a text. This does not need to be a polished, well-organized piece of writing. You may craft it in paragraph form or in a series of bullet statements. When you respond to a text, you are thinking about its broader implications. Was the text convincing? Why or why not? How does it relate to other texts you have read on the same subject? Can you connect the text to your own experience?

Though responding generally refers to the act of writing down your initial impressions of a text, you may respond by discussing your reading with your colleagues. Such discourse may help you to recognize how the new information may be meaningful or applicable to your own life, thus helping you to internalize concepts. In this way, the text becomes a dialogue. Worksheet 4 will help you to ask critical questions of the texts you read.

Worksheet 4. Critical reading

1. What does the text say?

a. What is the author’s bottom line/main argument?

b. What is the author’s stated purpose?

c. What are the supporting points?

d. What key questions does the author address?

2. What is the purpose of the text?

a. Who is the author?

b. What political, social, or professional goals might the author have for writing?

c. Who is the author’s intended audience? What is the audience’s agenda?

3. How does the author make their argument?

a. Is the author’s argument logical?

b. What type of style, tone, organization, and language does the author use?

c. Is the author’s real purpose different from the stated purpose?

d. What type of evidence does the author use to support their point (e.g., statistics, experience, examples, theory)? Is the evidence effective?

4. What are the broader implications of the text?

a. What are the main critical or analytical perspectives presented? How do they differ from other perspectives in the field?

b. How does the text relate to other course materials you have read? How does it relate to other research you have conducted?

c. What are the main issues for future consideration that the text raises?

CSG 5.4.7 Journaling: Keeping a Three-Column Journal

Another critical reading strategy is to keep a three-column journal. It is often helpful to create this in Microsoft Excel as a spreadsheet. In the first column, you would report a significant idea from the text. In the second column, you would analyze that idea or react to it in some way. Finally, in the third column you would connect the text to other ideas—research you have conducted or other texts you have read. Worksheet 5 is a template for how you might use this type of journal to take notes as you read.

Worksheet 5. Blank three-column journal template

|

Quote or paraphrase

from text

|

Analysis

|

Connection to other research

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Using these strategies will help you to read more critically. By encouraging you to focus on the meaning of the text and not merely the presentation of facts, these models may help you to connect complicated, recurring themes. While it seems as though using these strategies will take a lot of time, many readers find that using these strategies actually saves time: active and engaged reading strategies help you assimilate concepts for the long term, so you will not have to spend so much time rereading. The next two chapters will help to simplify the complex—and sometimes overwhelming—process of conducting scholarly research and writing a research paper.