PRINTER FRIENDLY PDF

Abstract: World War I was the first conflict where the U.S. Marines truly entered the American consciousness, particularly through the 4th Brigade’s accomplishments at Belleau Wood in June 1918. What is generally missing from the Marines’ story is the large number of U.S. Army officers who led Marine platoons in the brigade and often paid a heavy price for their service. This article examines how Army officers came to be assigned to the 4th Brigade and the backgrounds and performance of these “doughboy devil dogs” in the unit. It also offers some suggestions for why they largely disappeared from the narrative of the brigade’s service in World War I.

Keywords: great power competition, tripolar era, security assistance, Africa, China, Middle East, Russia

On 1 June 1918, the 2d Division was thrown into battle west of Château-Thierry, France, to shore up the wavering Allied lines in the wake of the Germans' Operation Blücher. On 27 May 1918, the German attack between Soissons and Reims had shattered the French defenses and pushed the Allies back more than 22 kilometers (km) as it surged toward the Marne River. Between 1 and 5 June, the 2d Division's soldiers and Marines fought off repeated German attacks before the commander of the French XXI Corps, General Jean-Marie Degoutte, ordered the Americans to counterattack to push the Germans back. The division's commander, Major General Omar Bundy, ordered the 4th Brigade to seize the German positions running from Hill 142 through Belleau Wood to Bouresches. Despite months of training and having served in a quiet sector of the French lines, the division's troops were not truly ready for their unsparing introduction to modern war. The Marines' frontal attacks against dug-in German infantry and machine guns were generally ill-supported by artillery and the green Americans paid a heavy price for their audacity. Losses were heaviest among the 4th Brigade's officers. On 6 June alone the 1st Battalion, 5th Regiment, lost roughly 90 percent of its commissioned ranks as it fought across open ground to take Hill 142. Among the dead was Second Lieutenant William Chandler Peterson. The 23-year-old graduate of the University of Illinois was just beginning his career as a Chicago architect when the United States entered the Great War. He was killed by machine-gun fire while leading his platoon in the 49th Company forward in the early hours of the attack.1 Although 6 June 1918 would hold the dubious distinction of being one of the bloodiest days in the Marine Corps' history, the 4th Brigade's ordeal was far from over. For 18 more days, the Marines battled to capture Belleau Wood from its tenacious German defenders. And for 18 more days, the enemy took a disproportionate toll of the brigade's officers. Second Lieutenant James Timothy, who had attended Vanderbilt University and the District of Columbia's Catholic College, was killed as he led a platoon in the 6th Regiment's 80th Company on 14 June. Some of the deaths from the battle were longer in coming. Second Lieutenant Laurence H. Gray was severely wounded by shellfire on 13 June while commanding a platoon in the 6th Machine Gun Battalion. Gray, a 1915 graduate of the University of Missouri Law School, never fully recovered from his wounds. He died on 26 January 1920, with his demise "being hastened by an impaired vitality sustained in service."2 Although it is well and good to speak of Tun Tavern, the Halls of Montezuma, and the Shores of Tripoli, it was not until the Battle of Belleau Wood that the Marine Corps truly entered the American consciousness. Marines are justly proud of their accomplishments in the battle and its lasting legacy on the Corps, but this action, and the sacrifices that it entailed, are not wholly a Marine Corps story. Peterson, Timothy, Gray, and approximately 15-20 percent of the platoon leaders in the 4th Brigade at Belleau Wood, were U.S. Army officers. This article will examine how Army officers came to be assigned to the 4th Brigade and the backgrounds and performance of these "doughboy devil dogs" in the unit. It will also offer some suggestions for why they largely disappeared from the narrative of the brigade's service in World War I. Although the article will focus only on the Army line officers in the brigade, it must be noted that more than 100 Army doctors, veterinarians, chaplains, enlisted signalmen, and other technical specialists also served in the unit during the war.

Army Officers in the 4th Brigade

In the early 1930s, Joel D. Thacker of the Muster Roll Section of Headquarters Marine Corps compiled a list entitled "U.S. Army Personnel (Including YMCA) Attached to Marine Corps Organizations." This list, compiled from Marine muster rolls and assorted orders and memorandums written during the war, contained the names of 198 Army officers, 110 Army enlisted men, and three Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) secretaries who were assigned to Marine units in France. Wherever possible, Thacker included the unit (down to company) that the soldiers served in, the dates of their service, and if they had been killed or wounded in the war. The nature of the often hurriedly produced wartime documents often left Thacker with little to go on. He recorded that a Lieutenant Hickman assigned to the 3d Battalion, 5th Regiment, was "slightly shell-shocked" on 24 June 1918 but could not provide the officer's first name, dates of service with the unit, or any information about what happened to him after he was evacuated from the unit.3 As might be expected with any project of this magnitude, Thacker also made mistakes. He noted that a Lieutenant John A. Burgess served with the 5th Regiment's 67th Company, but the U.S. Army Transport Service passenger lists for 1917 and 1918 do not show any officer by that name sailing to or from France. However, the passenger lists do show a Sergeant John D. Burgess serving in Company D, 67th Company, 5th Regiment, during the war. At times, Thacker simply got his details wrong. For example, he states that Captain Mortimer A. O'Hara served as the 6th Machine Gun Battalion's dentist from 1 April to 8 August 1918, yet passenger lists show that he did not sail for France until 26 July 1918, and 2d Division Special Orders 228 did not assign him to the unit until 2 September 1918. O'Hara did appear on the battalion's muster rolls for April, July, and August 1919, so Thacker may have simply made a transcription error in the years. Despite these minor issues, Thacker's list provides a good starting point for examining the extent that Army doughboys contributed to the 4th Brigade.4

Before examining the reasons that Army soldiers served in the 4th Brigade, it is first important to establish the extent to which they contributed to the unit. Although Thacker's list names 198 Army officers, when one filters out those who served with the Marines for short periods of training or temporary duty, the roll shortens considerably. For example, Thacker listed 27 officers from the 28th Division's 110th Infantry and the 4th Division's 58th and 59th Infantries who were attached to the 4th Brigade for training. Most of these officers were only assigned to the Marine regiments for less than a week of service in early July 1918. Sometimes, Army officers assigned to the 4th Brigade were simply transferred to other units so quickly that they made little to no impact on the unit at all. Second Lieutenants Fern M. Gumm, Edward R. Harris, and L. R. Hettick were with the Marines for less than a month when they were reassigned to the Services of Supply (SOS) Director of Transportation at Tours in March 1918. The insatiable manpower demands of the expanding SOS, rather than poor performance, seems to have been the reason for these infantry officers' hasty departure.5

After removing those officers whose time with the Marines was fleeting or whose information in Thacker's list was too incomplete and could not be verified through passenger lists and other sources, at least 90 Army line officers (not including chaplains or medical personnel) who served at least three months in the 4th Brigade or whose service was less than three months due to death or wounds while fighting with the Marines may be identified. All of these officers except one, Signal Corps Second Lieutenant George L. Townsend, were infantry officers. Of the 90 officers, 35 (38.8 percent) served in the brigade for three months; 12 (13.3 percent) served for four months; 17 (18.8 percent) for five months; 4 (4.4 percent) for six months; 10 (11.1 percent) for seven months; and 12 (13.3 percent) served for eight or more months. The average length of service for Army officers in the brigade was five months.

At first glance, it appears that Army officers spent a relatively short amount of time with the 4th Brigade, but it should be kept in mind that the brigade's wartime life, from its formation on 23 October 1917 to 11 November 1918, was just over 12 months. Although 35 of the officers served fewer than three months with the Marines, 7 of these men were killed in action during this period and 14 others left the unit due to wounds, gas poisoning, or shell shock. Thus, 60 percent of those with short periods of service had their time in the unit curtailed due to combat injuries. On the other end of the scale, three officers served for more than a year with the Marines. Captain Elliott D. Cooke was with the 5th Regiment for more than 14 months while Second Lieutenant Frederick G. Wagoner served in the 6th Regiment for 15 months. The Army officer with the longest service in the 4th Brigade was First Lieutenant Frederick J. Scheld, who was in the supply company and several of the line companies of the 6th Regiment from 5 February 1918 to 1 July 1919.

Why Assign Army Officers to the 4th Brigade?

But why were Army officers serving in what was ostensibly a Marine Corps brigade? The answer to this question is rooted in the challenges that the Marines faced in their wartime mobilization. When the United States entered World War I in April 1918, the Corps was a miniscule force of 462 commissioned officers, 49 warrant officers, and 13,725 enlisted. By the Armistice in 1918, the Corps had expanded to 2,174 commissioned officers, 288 warrant officers, and 70,489 enlisted.6 Although the Army experienced an even greater degree of expansion during the war, it was better positioned institutionally in the spring and summer of 1917 to cope with the challenges of a mass mobilization of officers than was the Marine Corps.

As early as 1913, Army chief of staff Leonard Wood had raised the need to start planning for a wartime expansion of the officer corps. He warned, "If we were called on to mobilize to meet a first-class power, we should require immediately several thousand officers; where are we to get them?"7 The Army's experience operating the prewar "Plattsburg" citizen's military camps of instruction in 1915 and 1916 gave the Service some limited insights into selecting and training a large number of officer candidates.8 The camps also highlighted the inadequacy of the Plattsburg training program in New York and led the Army to develop and test a three-month training course for officer aspirants at Fort Leavenworth in late fall 1916. With a tried-and-tested course in hand, the Army was able to quickly establish 16 officer training camps (OTCs) across the nation by 8 May 1917. Although the training at these camps was woefully insufficient to prepare their graduates for the realities of modern war, they were generally successful in filling combat units with junior officers with the basic skills to begin the training of the ever-expanding ranks of volunteers and draftees. What the OTCs lacked in realism, they made up for in numbers. On 11 August 1917, the first OTCs commissioned 21,000 officers, and a second round of OTCs produced another 17,237 officers in November 1917. In other words, each of these two camps commissioned more officers than the total strength of the Marine Corps on 6 April 1917.9 By the end of the war, the total number of officers that the Army commissioned for the conflict was more than double the total number of Marines in the ranks at the time of the Armistice.

While the Army experimented with ways to expand its officer corps from 1913 to 1916, the Marine Corps devoted little thought to this issue. This failure to plan for a large-scale mobilization was influenced by the Corps' prewar missions, its operational commitments in the years leading up to the war, and its traditional approach to officer procurement. From the 1890s to the brink of the Great War, the Corps fought hard to establish a clear-cut role in the nation's security as it countered powerful voices within the Navy that questioned its utility in the emerging age of long-range fleet engagements. By the first decade of the twentieth century, the Corps had embraced the role of being a landing force to fight small-scale contingency operations and as an advanced base force to seize and/or defend the overseas ports and facilities vital to the U.S. Navy's operations.10 The decade prior to the American entry into the war was also an exceptionally busy one for the Corps. It was actively engaged in stability, security, and occupation duties in Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, Guam, Samoa, the Philippines, and Beijing; had landed forces to seize Vera Cruz in 1914; participated in advanced base exercises; and provided detachments on more than 50 Navy ships. As historian Allan R. Millett observed, "Like the nation it served, the Marine Corps was too absorbed with its own problems to believe that it would someday fight in France."11

Given the size, missions, and operational commitments of the Marine Corps in the years leading up to the United States entering the war, it is little wonder why it devoted almost no thought or planning to the selection and training of a large number of officer candidates. In fact, an 11 July 1916 memorandum from Commandant of the Marine Corps Major General George Barnett to Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels shows that the Commandant was more concerned with how the Corps would fill the increase in officer strength from 344 to 597 under the pending congressional authorization bill than with any possible wartime expansion. Barnett noted that it would take the Corps 13 months to bring in the 203 additional officers that the bill allowed, but that the time could be cut to three months "under war conditions."12 Nowhere did Barnett envision a major increase in the Corps' strength or the challenges of leader procurement that such a mobilization would entail. Despite this reality, when it became clear that the United States would send a large expeditionary force to France, the Marines fought hard to be part of the contingent. However, the expansion that such a commitment entailed caught the Corps flat-footed without a system and infrastructure for officer candidate training.

In early May 1917, while the Army was receiving thousands of candidates into its newly established OTCs, the Corps was scrambling to purchase land at Quantico, Virginia, to serve as the site of its officer school, replacement battalion mobilization cantonment, and Overseas Training Depot. Barnett's decision to build a Marine-only training base was the result of hard experience. The Corps' previous junior officer schools had been constantly relocated at the whims and needs of the Navy. Unfortunately, the time it took to build the Quantico base from the ground up delayed the start of its officer school until July 1917. Those officers who had flocked to join the ranks before that date were temporarily assigned to the Marine rifle range complex at Winthrop, Maryland; Mare Island and San Diego, California; or Parris Island, South Carolina, to receive a very basic level of indoctrination and training.13 The Corps later sent most of the Marines attending these camps to Quantico once the facilities there were up and running. However, to meet the pressing need to bring the 5th Regiment up to strength so it could deploy to France in June 1917, the Corps chose to send some newly commissioned officers to the regiment with only the barest of training. Most of these officers seem to have been graduates of the Virginia Military Institute (VMI), the Citadel, or other distinguished military colleges and thus were presumed to have undergone a degree of military instruction. One such officer, Lemuel C. Shepherd Jr., chose to enter the Marine Corps after failing to receive one of VMI's allocations for Army commissions. He admitted that his training prior to sailing for France consisted only of two weeks of rifle instruction at Parris Island. When he arrived in France, he had only been in uniform for a month and a half.14

Although the rapid commissioning of men like Shepherd covered the Corps' most pressing need for officers, the Corps still faced a long-term systemic challenge in producing junior leaders. Delays in getting the Quantico schools operational and the limited numbers of candidates that the new post could accommodate slowed the commissioning of new Marine officers. As the Marine regiments assigned to the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) had to mirror the organization of Army companies and battalions, the ballooning size of those echelons required even more junior officers, and thus exacerbated the Corps' personnel problems. Despite these issues, the Quantico OTC still commissioned 300 officers on 15 July 1917 and another 91 on 15 August 1917. As their officer training was only two months in duration (rather than the three months required in the Army), many of these officers remained at Quantico until the spring of 1918 undergoing further instruction in the Overseas Depot or in the replacement battalions forming at that station. High officer casualties that summer led the Corps to hold a second OTC at Quantico in August 1918, but its 432 graduates were not commissioned until after the Armistice.15

The other factor that delayed the commissioning of Marine officers in 1917 was Commandant Barnett's decision to change how the Corps would select officers for the remainder of the war. On 4 June 1917, he directed that "owing to the unusually large number of men of excellent education and fine attainment who have enlisted in the Marine Corps since the outbreak of the war all vacancies occurring during the war will be filled by appointment of meritorious noncommissioned officers who distinguished themselves in active service." As J. Michael Miller, the former lead historian of the Marine Corps History Division, noted, Barnett's "fateful order altered the influx of Marine officer candidates from across the United States and slowed the training of officers for the Marine Brigade in France. . . . The ensuing shortfall [of officers] eventually resulted in army officers commanding Marine platoons in 1918."16

When the 5th Regiment landed in France in late June 1917, the AEF was in the midst of a massive restructuring of its organizations. While a full-strength prewar Army infantry regiment contained 51 officers and 1,500 soldiers, by early 1918, the regiment had grown to 112 officers and 3,720 soldiers. As the Marines had to conform to the Army's regimental organization, the delays in commissioning new Marine officers left the 5th Regiment short of leaders to fill these new requirements. It is unclear from the existing record if the 5th Regiment requested Army officers to fill its ranks, or if the staff of the 2d Division saw the unitÕs shortfall and proactively addressed the Corps' personnel issue, but on 11 November 1917 the 2d Division assigned 30 Army Reserve officers to the regiment.17

The 6th Regiment faced similar shortages of officers as it slowly formed over the fall of 1917 and winter of 1918. On 15 January 1918, the commander of the 4th Brigade, Brigadier General Charles A. Doyen, directed the 5th Regiment to "transfer half of the Army Reserve Officers now on duty in your Regiment to the 6th Regiment." Although the 5th Regiment only sent nine Army lieutenants to its sister regiment, these officers would not be the lone doughboys in the 6th Regiment for long. The 2d Division allocated the 6th Regiment 16 additional Army Reserve lieutenants on 12 March 1918 and 20 more on the 27th. The last unit formed in the 4th Brigade, 6th Machine Gun Battalion, also received its fair share of Army officers. On 27 March 1918, the 2d Division assigned four Army Reserve lieutenants to the unit, and five more doughboy officers followed shortly thereafter.18

It seems that the Army officers generally fit in well with the Marines. Wallace Leonard Jr., a graduate of the Amherst College Class of 1916 and the 2d Plattsburg Barracks OTC, was particularly taken with his new comrades. In a letter to his parents, he proclaimed

These are the finest soldiers in the world. The more that I see of my Marines the fonder I grow of them. They are a cocky lot, but every man is a soldier. They are as proud as Lucifer, but their equipment always shines.19

Leonard's high opinion of the sea soldiers was also shared by an Army machine-gun officer identified only as "Wayne." He wrote home shortly after the Battle of Belleau Wood

These Marines are epic fighters. . . . Back in the towns they would growl like bears at busted bunks or the quality of the beer, but take them upon the line, work them day or night under shell fire, on bum food for a month, and you never heard a word. They will get tired and strained and swear like the Devil, but growl or shirk when called to duty, they don't, these Marines.20

At least two of the Army Reserve officers were so taken with the Marines that they requested transfers to the Corps. On 4 March 1918, Second Lieutenant Calvin L. Capps asked to be commissioned in the Corps. Capps, who was one of the officers transferred from the 5th Regiment to the 6th Regiment on 17 January 1918, made a favorable impression on the three company commanders under whom he served. All endorsed his transfer, with First Lieutenant W. A. Powers noting that Capps "has the ability to handle men, a very good understanding of the work and is able to impart what he knows to those under him. In my opinion he would make an excellent Officer for the Marine Corps." Although the 6th Regiment's commander, Colonel Albertus W. Catlin, recommended approving the transfer, on 16 April 1918, the AEF adjutant general informed the I Corps commander that the headquarters had denied the move, stating, "There is no apparent reason why this transfer is necessary in the best interest of the service." Despite this setback, Capps continued to soldier on well with the 6th Regiment until he died of wounds sustained at Belleau Wood on 12 June 1918.21

The other Army Reserve officer seeking to transfer Services was Second Lieutenant Herbert Jones, who had been assigned to the 6th Machine Gun Battalion on 28 March 1918. In his 30 June 1918 transfer request, Jones stated, "Having seen service with the Marines in their recent operations in the trenches near Verdun, and in their present operations in the Château-Thierry sector, I would like to remain with them." His company commander, Captain George H. Osterhout Jr. recommended that the Commandant approve Jones's request, noting that during the Belleau Wood fighting the lieutenant had "acquitted himself with great gallantry, and I believe he would make a good Officer for the Corps." Before any action could be taken in the matter, Jones was killed in action near Soissons on 19 July 1918.22

Army Reserve Officer Backgrounds and Training

The Army officers assigned to the 4th Brigade arrived in France in three waves. Twenty-six (28 percent) landed in September 1917, 59 (66 percent) arrived in January 1918, and 5 (6 percent) landed in February 1918. The vast majority of these officers arrived as "casuals"—soldiers not assigned to a specific unit. As they were assigned to France relatively early in the formation of the AEF, it is not surprising to discover that all of the officers whose training camps could be identified graduated from the first two iterations of the Army's OTCs. Thirty-three (47 percent) were commissioned from the first OTCs in August 1917, and 37 (53 percent) graduated from the second OTCs in November 1917. Although the officers who were later assigned to the 4th Brigade attended nine different training camps, 75 percent of them had been commissioned from only two camps: Fort Sheridan, Illinois (51 percent of total), and Plattsburg Barracks, New York (24 percent of total).23

The early arrival and commissioning training of the officers assigned to the 4th Brigade is important for two main reasons. The men commissioned out of the first two OTCs tended to be taught by a greater percentage of regular Army instructors than the OTCs held in 1918, and the candidates themselves underwent a more rigorous selection process and had higher levels of education than in subsequent camps.24 Ralph B. Perry, the secretary of the War Department Committee on Education and Special Training, observed that the graduates of the first OTCs were

of the highest quality in physique, intelligence and spirit. They were put on their mettle through being made to feel up to the very last moment that their commissions were doubtful. Most important of all, they were under close observation and could be selected for [their] personal qualities.25

He further noted that their "education, experience and natural aptitude" made them "especially qualified for leadership."26

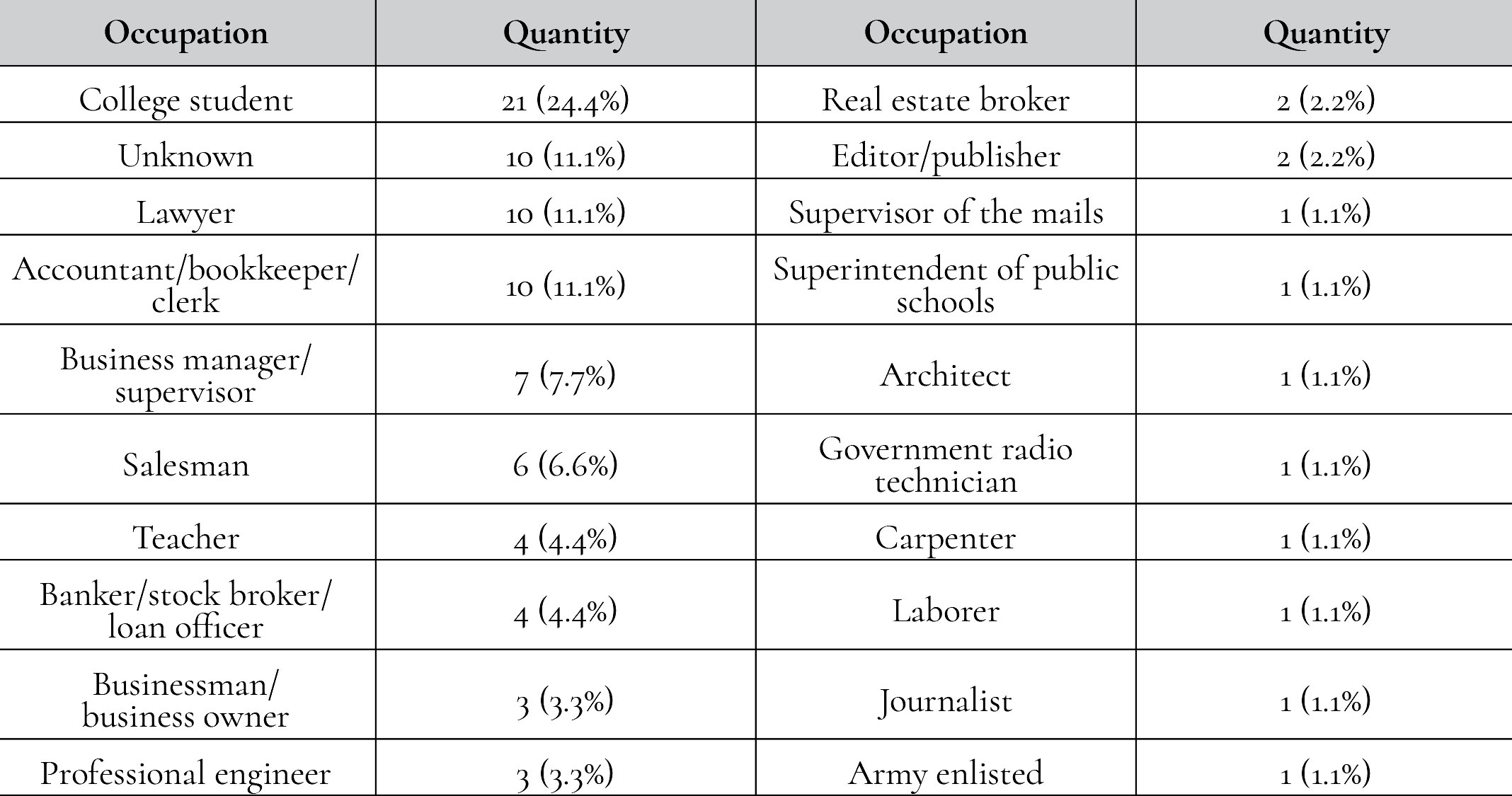

Perry's assertions about the qualities of these early graduates are borne out in the available statistics on the educational background and prewar occupations of the 90 Army line officers in the 4th Brigade. Of the 56 cases where it was possible to discover the educational background of the officers, 30 were college graduates, 24 had some college or were college students at the time they entered the OTC, and two were educated at public schools. Many of the college students or graduates had attended some of the nation's most prestigious institutions, such as Harvard, Cornell, Johns Hopkins, Tufts, and Columbia Universities, and Dartmouth and Amherst Colleges. Although it was possible to uncover the educational backgrounds of only 62 percent of the officers, the occupations that they held prior to the war (table 1) indicate that the vast majority of them were from solid middle- or upper middle-class backgrounds. Given these occupations, it is safe to assume that in many of the cases where the officers' education level was unknown, they possessed at least a high school or some degree of higher education.27

Table 1: Prewar occupations of Army officers serving in the 4th Brigade

Source: Created by Richard S. Faulkner

Another reason that the officers' early arrival in France was important was because it afforded them the opportunity to attend one or more of the schools that the Allies and the AEF established to close the wide doctrinal and technological gaps between what the officers had learned in the United States and the realities of combat on the western front. Pershing and his staff were well aware that stateside training in 1917 was often hamstrung by shortages of automatic rifles, grenades, machine guns, and other key weapons that had emerged during the war, as well as their understanding that a simple lack of knowledge and realism had plagued much of the instruction of the novice officers. Most of the Army officers in the 4th Brigade first attended one or more of the AEFÕs schools before reporting for duty with the Marines. For example, after Second Lieutenant Calvin Capps arrived in France in September, he attended the 1st Army Infantry Officers School and courses with the British Army on bayonet fighting, sniping, and the Stokes mortar. Likewise, Army Reserve officers assigned to the 6th Machine Gun Battalion attended AEF machine gun schools before reaching the Marines.28

Although faith in American know-how and methods at times weakened the effectiveness of the AEF's schools, a number of officers who later served with the Marines benefited from the direct tutelage of the French or British. One such officer was First Lieutenant Wallace Leonard Jr. Upon arriving in France, Leonard reported to the French infantry officer's school at Châtillon-sur-Seine for a month of training. The final exam of this instruction was spending several days in French trenches at the front. The young officer got his introduction to war when he witnessed a trench raid by 250 Germans on his segment of the line.29

The education levels, backgrounds, and training experiences all indicate that there was little to no difference between the quality of the newly commissioned Army officers and their Marine comrades in the 4th Brigade. This counters an assertion made by historian Peter F. Owen, who maintains that the aforementioned Leonard "was unpopular with some of the marines, an unfortunate situation aggravated by the fact that Leonard was an army reserve officer." Owen explains Leonard's presence in the 6th Regiment by noting, "While marine lieutenants attended schools, army officers of mixed quality were often assigned to 2/6 [2d Battalion, 6th Regiment] as temporary replacements."30 The Marines at the time were not so quick to discount the ability of their Army peers. On 22 February 1918, Second Lieutenant Clifton Cates, a platoon leader in the 2d Battalion, 6th Regiment, and future Commandant of the Marine Corps, wrote home, "We have a new lieutenant assigned to our company; a Lieut. Capps, from the U. of N.C. He seems to be a nice fellow and is very good, as he has been over here for six months."31 Leonard also had his supporters. His company commander, Captain Randolph T. Zane, commended him for leading the 79th Company's second platoon on Bouresches on 6 June 1918, noting that he advanced his unit "through the most intense artillery and machine gun fire to a position about three hundred yards beyond the town, having only ten men left, intrenched [sic] and remained until the remainder of the company entered Bouresches an hour or so later." Upon Leonard's transfer from the unit, Zane wrote a letter of recommendation to his gaining command, stating that he "could not speak too highly of the courage, coolness, professional abilities, and attractive personality of this officer." Zane went on to note, "Having him under [my] command was a great satisfaction and pleasure, and his loss to the company was most sincerely regretted by officers and men alike."32

While it was true that the training of Army officers was far too short and unrealistic to adequately prepare them for what they faced in France, there was little difference in the wartime instruction of officers between the two Services. In 1918, Commandant Barnett reported to the secretary of the Navy that "the training at the camps has been most intensive and thoroughly competitive."33 This was not a view shared by the Marine officers themselves. Second Lieutenant Robert Blake was critical of the depth and quality of his training at Quantico officers' school, describing it as "very primitive, principally boot camp drill" with "some class work." He remembered that one of the officers running the Quantico school, Captain Charles Barrett, later confessed to him that while "he received a letter of commendation for the work that he did in those officers' training schools, I should have gotten a general court martial." Blake philosophically noted, "Of course it wasn't his fault. . . . They just didn't know."34 The era's Army officers often mirrored Blake's views of their own training. Rather than engage in Service chest-thumping, it is wise to paraphrase Abraham Lincoln's admonishment to Major General Irvin McDowell in 1861: the Army officers were green, the Marine officers were green, they were "all green alike."35

Owens's point that the Army Reserve officers were merely "temporary replacements" in the unit so the Marines could go to school also bears further investigation. The surviving records of the 2d Division and the 4th Brigade offer an incomplete and ambiguous picture of the Army Reserve officers' status in the brigade. As discussed later in this article, there also appears to have been a different level of acceptance of these officers between the 5th and 6th Regiments. On 23 December 1917, the acting commander of the 6th Regiment, Lieutenant Colonel Hiram I. Bearss, directed

Officers of the U.S. Reserves doing duty with the Regiment were ordered here for the purpose of instruction. Battalion commanders will please see that these officers are afforded the same opportunity for instruction in theoretical work and practical in command of platoons and companies as afforded officers of like rank in the Marine Corps. These young officers will probably be scattered throughout the service and the organization to which they were attached for instruction will be judged by the efficiency.36

Both the 5th and 6th Regiments initially seemed to have viewed the assignment of Army Reserve officers to their units as temporary arrangements, but both units took the mission of training them seriously. War Department General Orders 83 required that all officers "not reported on organizational returns" on duty in France or Britain were required to submit a monthly report to AEF Headquarters detailing "the duties on which [they were] engaged." From the reports, it is possible to see the variety of instruction that the Army Reserve lieutenants received in the early months of their service with the Marines. Second Lieutenant Benjamin Brown, who served with the 5th and 6th Regiments from November 1917 until August 1918, reported in December 1917 that he received "instruction in a very practical and thorough nature" in "maneuvers in the French style of attack and defense" at the regimental to platoon level, the "many varieties of liaison," and the "actual occupation of a company sector of trenches with drill in entering and leaving the trenches, and responding to the "alert'." Second Lieutenant James Cooper likewise reported a diverse array of training. In between studying map reading, field sanitation, and the control of venereal disease, he also spent time under the watchful eyes of French officers learning "attack formations, advancing in connection with barrage fire," and Òdirecting the course of an attack by use of compass." One focus of instruction, "storming a machine gun post using hand and rifle grenades," would later come in handy at Belleau Wood. Like any of his fellow Army officers, Cooper believed that his training was "highly practical and instructive and the time well spent."37

Role and Service of 4th Brigade Army Officers

The confusion over the status of the Army Reserve officers was also evident when the 2d Division directed the 4th Brigade to temporarily assign some of its Army officers to assist in the training of the 32d Division. The division directed that the 5th and 6th Regiments send six Army officers each for this mission. However, when the officers returned to the 4th Brigade, the 6th Regiment questioned their reassignment to the regiment. On 17 May 1918, Major F. E. Evans, the adjutant of the 6th Regiment, wrote to the 2d Division assistant adjutant

Six (6) U.S. Reserve officers who formerly served with this organization have been ordered to rejoin it from the 32nd Division. . . . As we have been advised that all the reserve officers were to be transferred from this organization to other organizations. . . . [and] it is requested that if possible you advise me by memorandum whether the order in regard to replacement of reserve officers has been cancelled.38

The 5th Regiment took a different approach and chose not to ask a question of the division to which they did not want to know the answer. Its commander never questioned the return of the officers to the unit or having them command the regiment's platoons. The 5th Regiment seemed to have taken the mission of training the 32d Division seriously for they sent some of their best Army Reserve officers (Joseph Brady, Jerome Goldman, Robert Lineham, John Revelle, and Arthur Tilghman) to the 32d Division. Despite a flurry of orders at the time directing the regiment to send Army Reserve officers to serve as instructors in the United States or to transfer them to other 2d Division units, the 5th Regiment chose to retain all five of the officers in the regiment when they returned from the 32d Division. One of the officers, Joseph Brady, a former journalist, was gassed on 7 July 1918 and, on his release from the hospital, remained with the 5th Regiment until it returned to the United States in August 1919. For four others, the regiment's decision proved more fateful. Less than three weeks following their return to the 5th Regiment, two of the officers were killed (Goldman and Peterson) and two others were wounded (Lineham and Tilghman) in the fighting at Belleau Wood.39

Although the official status of the Army Reserve officers was open to debate, what is clear from the record is that the units of the 4th Brigade assigned them to important positions within their organizations. On 29 May 1918, as the 4th Brigade was hurrying to the front to fill holes in the French lines, its war diary reported that the unit had 278 officers present for duty. On that date, there were 75 Army Reserve officers assigned to the brigade. Assuming that these officers were included in the war diary numbers, Army officers made up nearly 27 percent of the brigade's commissioned strength.40 Unfortunately, neither the brigade's surviving records nor the unit muster rolls from the period offer a complete picture of what assignments these officers held. However, the existing reports give some indication of their responsibilities. The commander of the 5th Regiment's 55th Company (in which Lemuel Shepherd served as the company executive officer) reported that when his unit went into action at Belleau Wood, half of his platoon leaders were Army officers. The company's 3d platoon was commanded by Second Lieutenant Arthur Tilghman, and the 4th platoon was led by First Lieutenant Robert Lineham. While he jumped at the opportunity to seek an Army commission, Tilghman was no stranger to the sea Service. Prior to the war, he served two years in the U.S. Navy and left the Service as a petty officer to become an office manager in a Chicago insulation company. During the vicious fighting around Lucy-le-Bocage, both officers received serious wounds. Both also briefly returned to the 5th Regiment after recovering from their injuries. Lineham was ultimately transferred to the 23d Infantry in August 1918. Tilghman returned to the Marines in time to participate in the Aisne-Marne campaign. During the fighting in late July, he was gassed with phosgene and had his left forearm shattered by shrapnel. After three months in the hospital, the Army determined that he was unfit for further combat service, and he ended the war commanding the 1st Prisoner of War Escort Company. Unfortunately, Tilghman's wounds also weakened his health. After a case of influenza gave way to cerebrospinal meningitis, he died in Tours, France, on 12 February 1919.41

In other cases, the records noted that Army Reserve officers served as platoon leaders or were otherwise commended for leadership in combat. For example, Lieutenant Colonel Frederick M. Wise, the commander of the 2d Battalion, 5th Regiment, recommended that Second Lieutenant R. H. Loughborough be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his gallantry at Belleau Wood. Wise noted that on 13 June "after all the other officers of his company had become casualties, [Loughborough] assumed command and by his personal example of extraordinary heroism led his men forward and assisted in capturing many machine guns."42 Loughborough was not the only Army officer to rise from platoon leader to company commander during the fighting at Belleau Wood. First Lieutenant Elliott Cooke was transferred from the 18th Company and assigned to command the 55th Company after most of that unit's officers had become casualties. As company commander, "He handled it in a manner which demonstrated absolute control of new men, with excellent results in checking the enemy." Colonel Harry Lee, the commander of the 6th Regiment, was so impressed with the performance of First Lieutenant Frederick Wagoner at Belleau Wood and other operations that he recommended him for promotion to captain. Lee based his recommendation on the fact that Wagoner had performed well as both a platoon leader and as second in command of the 76th Company in combat. Lee reported that "he has at all times distinguished himself by the able way in which he handled his men under fire" and that "he has repeatedly demonstrated his ability to command a company and is the type of officer of whom you can expect results when he is given a mission to execute."43

Reports explaining the deaths of officers in battle also tended to list the positions that the Army Reserve officers held when they became casualties. The commander of the 5th Regiment's 43d Company reported that at the time of his death on 11 June 1918, Second Lieutenant Robert S. Heizer was leading members of his platoon against German machine guns that were firing into the flank of his unit. His commander noted that Heizer's efforts "were eminently successful, the machine gun nests being completely destroyed and the crews killed or taken prisoner," and thus "this dangerous advantage on the part of the enemy was eliminated." At age 30, Jerome L. Goldman was older than most of his junior officer peers, and this maturity led his company commander to select him to serve as his second in command. Goldman was killed by machine gun fire on 12 June while "leading his men in the attack" on the hunting lodge in the northwest of Belleau Wood. His commander would later write that Goldman's "efforts contributed to the measure of success that crowned the efforts of the Marines at that place to a large degree."44

Based on the available records, it is possible to make a conservative estimate that 15 to 20 percent of the platoon leaders in the 4th Brigade in the first two weeks of fighting at Belleau Wood were Army officers. Their service as leaders was also evident in their sacrifice. Five of the Army Reserve officers serving with the 5th Regiment and four serving with the 6th Regiment were killed in action or died of their wounds during the Belleau Wood fighting. Another 24 Army officers were wounded, with three more being gassed, and two "shellshocked" during the fighting. In all, 38 of the 75 (50 percent) Army lieutenants who went into the battle became casualties. Three more Army Reserve officers would later die while leading platoons during the Aisne-Marne and Saint-Mihiel campaigns.45 Although references to the officers are rather scarce in the narratives of the war's Marines, the passages where they do appear tend to be positive of the officers' leadership and sacrifices. Don V. Paradis noted the sadness that his company felt at the loss of the Army Reserve officer killed while assigned to his unit. Paradis noted that "he was surely a brave man and was already well liked by the whole company" and added that the Marines commenced to "pick off any moving Germans in exchange for the lieutenant's death."46

Removal of Army Reserve Officers from the 4th Brigade

Despite the Army Reserve officers' service and sacrifice with the Marines, the 2d Division and some senior Marine officers had worked steadily to purge them from the ranks of the 4th Brigade. The push to reassign the Army officers from the unit had slowly gained momentum in the two months prior to the start of the fighting at Château-Thierry. In the winter of 1918, the AEF Headquarters agreed to send "seasoned" AEF officers to serve as instructors and leaders in the divisions undergoing training in the United States. The Army Reserve officers of the 4th Brigade were easy pickings for these transfers. In compliance with the headquarters and 2d Division directives, on 2 April 1918, the 4th Brigade transferred eight of its officers to the states and in May ordered another eight of its Army lieutenants to return home. All of the selected officers had "completed a course of instruction at corps schools, A.E.F. and having had a tour of duty at the front" were well suited "to assist in the training of organizations" in the states.47

Perhaps the most unfortunate and controversial transfer of Army Reserve officers from the 4th Brigade came in June 1918 in the midst of the fighting at Belleau Wood. On 8 June 1918, the brigade's commander, Army brigadier general James G. Harbord, noted that "heavy losses of officers compared to those among the men are most eloquent as to the gallantry of our officers" but went on to caution his subordinates that "officers of experience are a most valuable asset and must not be wasted."48 Despite his admonishment to his commanders to conserve their experienced leaders, Harbord and the staff of the 2d Division were rapidly transferring combat-tested Army Reserve officers from the brigade. Part of this was due to the AEF's ongoing drive to rotate veteran officers back to the states. Thus, in compliance with headquarters and division directives, on 4 June 1918, the 4th Brigade ordered eight Army officers to return home.49

If Harbord was so concerned about the loss of leaders in the brigade, one wonders why he did nothing to protest these transfers. One explanation for his lack of action may have been pressure from his own senior Marine officers. After decades of fending off the Army and Navy's attempts to absorb or abolish them, the Marines had developed a driving desire to cement their place in the nation's defense establishment. Heather Venable recently argued that in the decades prior to World War I the Marine Corps "deliberately crafted" a public image of itself as an elite fighting force that provided the nation with a vital and distinct military capability. Commandant Barnett and his senior subordinates viewed the Marines' service in the Great War as essential to solidifying this image by keeping that service in the public's mind to ensure the Corps' long-term existence.50 Having Army officers leading Marine platoons certainly did not mesh well with Barnett's vision.

In the two weeks prior to the Belleau Wood battle, Colonel Albertus Catlin and his adjutant were particularly active in advocating for the removal of Army Reserve officers from the 6th Regiment. On 17 May, Catlin informed the division commander of his understanding that "all Army reserve officers will be detached and their place filled by Marine officers." The same day, Catlin's regimental adjutant pressed the 2d Division assistant adjutant on the status of the officers in his unit and reminded him that he was ready to have their "vacancies filled by Marine officers from [the] replacement [depot]."51 Between late February and early May 1918, the Marine Corps sent three replacement battalions to France to provide the 4th Brigade with officers and enlisted troops to replenish its anticipated combat losses. With the arrival of these battalions, Catlin seems to have grasped the opportunity to transfer as many Army Reserve officers as possible to make room for the newly arrived Marine officers, even when this meant replacing Army leaders who had trained and fought with the 6th Regiment with green platoon leaders.52

Being pulled out of action to return to the states was bewildering to the officers involved. Leonard informed a reporter from the Boston Globe, "I couldn't have been more surprised if they'd ordered me to be shot at sunrise. . . . Imagine starting for home at a moment's notice from a cellar in Bouresches. I won't say the thought of going home hurts me any, but well, I'd rather have stuck around and seen this thing through."53 It is interesting to note that while the 6th Regiment transferred 11 Army Reserve officers to the states or other units in the 2d Division during the Battle of Belleau Wood, the 5th Regiment only transferred four of its Army leaders during the period and somehow managed to delay the order to send its quota of four officers back to the states until after the fighting.

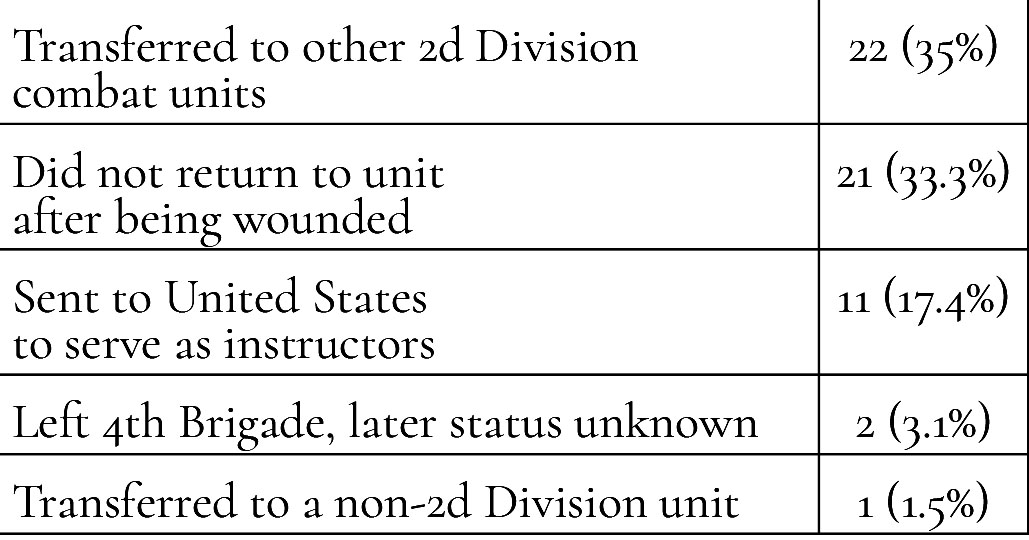

The arrival of the Marine officer replacements and casualties in both the 4th Brigade and the 2d Division's 3d Brigade in June, July, and August of 1918 began the rapid decline of the number of Army Reserve officers serving with the Marines. Table 2 illustrates the fates of the 63 officers who survived their service with the 4th Brigade.

Table 2: Disposition of Army Reserve officers after Belleau Wood

Source: Created by Richard S. Faulkner

The 5th and 6th Regiments each had three Army Reserve officers (a total of 9.5 percent) who remained with them into 1919. On 7 August 1919, the 2d Division ordered that all of the remaining Army officers in the 4th Brigade be relieved from duty with the Marines and report to the divisional adjutant for reassignment.54

The officers transferred to the 2d Division's 9th and 23d Infantry Regiments and the 4th and 5th Machine Gun Battalions generally performed well in their new assignments. Thirteen of these 22 officers were awarded Silver Star Citations and the French Croix de Guerre for their leadership and bravery in combat. Two of them were also awarded the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC), the United States' second-highest award for valor. Second Lieutenant Charles Heimerdinger earned his DSC, a Silver Star Citation, and a Croix de Guerre on 2 November 1918 at Landres-et-Saint-Georges for leading a patrol that destroyed enemy machine guns and personally fighting off the enemy to enable his wounded to be removed from the battlefield. First Lieutenant Joseph W. Starkey's combat record after leaving the Marines was even more impressive. The Tennessee native was awarded a Silver Star Citation at Château-Thierry and two more while serving with the 9th Infantry at Soissons. He was awarded the DSC and a Croix de Guerre with bronze palm for being cited in Army dispatches and was made a Chevalier of the Legion d'Honneur by the French government for extraordinary heroism at Mont Blanc. On 8 October 1918, despite being wounded and "regardless to danger to himself," Starkey led his men through heavy machine-gun and artillery fire in a successful attack against the German line. In the process, he suffered a second wound. It should be noted that 21 other officers received awards while still serving with the Marines.55

Although the majority of the officers performed satisfactorily in the 4th Brigade, as can be expected, not all of them consistently covered themselves with glory. On 3 May 1918, the commander of the 2d Division directed that Colonel Catlin reprimand Second Lieutenants Robert L. Renth and William H. Osborn for their failure to properly supervise their platoons during a gas attack on 13 April 1918. The attack resulted in the deaths of 23 Marines, scores more wounded, and the relief of the commander of the 1st Battalion, 6th Regiment. The division commander warned the two Army Reserve officers that "unless their attention to duty shows immediate and marked improvement, steps will be taken to terminate their commissions."56

Renth and Osborn were not alone in their failings. In May 1918, the commander of the 6th Marine's 83d Company, Captain A. R. Sutherland, reported that Second Lieutenant Benjamin Brown "did not have the necessary requisites to command men due to his inability to hold the attention and to command the respect of those under him. Also, that he had the unfortunate quality of antagonizing all men he tried to instruct." Although Sutherland recommended that Brown be removed from the regiment, his replacement, Alfred Noble, asked Catlin that the Army officer be given a second chance. Noble noted that upon taking command of the company, he reassigned Brown to "details such as checking on property, supervision observation posts, and such other details which called for mathematical calculations and perseverance." Noble recommended that while he would "never recommend him to command troops," Brown had proven himself "persistent, earnest, and reliable" in his new duties and would serve ably as the assistant battalion quartermaster. Catlin was unmoved by Noble's plea and recommended that Brown be moved to the Services of Supply or sent before an elimination board. Fortunately for Brown, the 6th Regiment entered the fighting at Château-Thierry before Catlin's recommendation could be implemented. During the fighting, Brown served as the 3d Battalion's quartermaster and "showed marked ability in the work assigned." The battalion commander, Major Berton Sibley, reported that he "personally superintended the delivery of rations . . . into the line, and through his efforts the 3rd Battalion did at no time suffer from the non-delivery of supplies."57

Although Brown's commanders accurately deduced his strengths and weaknesses, the case of Second Lieutenant Fred Becker demonstrated that the first impressions of the Marine Corps officers were not always accurate. Becker was the first All-American football player to come out of the University of Iowa, but he left college soon after the war began to enroll at the 1st Officer Training Camp at Fort Snelling, Minnesota. Becker was two months shy of his 22d birthday when he landed in France and was assigned to the 5th Regiment in September 1917. Becker had a rough time in his early months with the unit. On 1 May 1918, his company commander reported that the young officer "has not the proper sense of responsibility and lacks the proper judgment to handle situations which a platoon commander must handle independently." Although Becker was removed as a platoon leader, high officer casualties in the June fighting quickly led to his reinstatement. Becker seems to have rebounded from his early lackluster performance. He was wounded during the Belleau Wood fighting on 11 June, and on his recovery returned to the 18th Company to serve as a platoon leader. On 18 July, during the Second Battle of the Marne, Becker was killed after he advanced alone to destroy a machine gun nest that was holding up the Marines' advance near Vierzy. For this action, he was posthumously awarded the DSC and the Croix de Guerre with a silver star for being cited in division dispatches for "extraordinary heroism" that prevented "the death or injury of many men of his command."58

Army Reserve Officers' Place in 4th Brigade History

The last major issue to address is why the Army Reserve officers have largely disappeared from the historical narrative of the 4th Brigade. Even historians who offered sympathetic portrayals of the Army officers, such as George Clark and J. Michael Miller, tend to only mention them in passing. Part of the issue was that the officers themselves left few written accounts of their service with the Marines—except Elliott Cooke. Cooke was an excellent soldier with a swashbuckling background that appealed to the Marines. He allegedly ran away from home at age 14 to serve as a hired gun for the United Fruit Company in Central America and served as a mercenary in the Mexican Revolution before enlisting in the U.S. Army in 1914. His sterling combat record while serving with the 5th Regiment from November 1917 to February 1919 earned him a regular Army commission after the war. In 1937 and 1938, Cooke published two articles on his wartime experiences in Infantry Journal. In 1942, Edward S. Johnston included Cooke's articles in his compilation Americans vs. Germans: The First AEF in Action. This exposé, the ease of locating his account, and the fact that Cooke rose to the rank of brigadier general during World War II, ensured that he has been included in most of the secondary histories of the 4th Brigade.59 No other Army Reserve officers seem to have published memoirs, and their existing letters and other records are scattered across numerous state and university archives.

Another reason for the near anonymity of the officers was that the 4th Brigade's wartime personnel records were either incomplete or cobbled together. Only half of the 90 Army line officers who served at least three months in the 4th Brigade or whose service was less than three months due to death or wounds while fighting with the Marines are listed on any of the unit's wartime muster rolls. Seventeen of the 45 (37.7 percent) only appeared on an addendum roll from June 1919 that sought to reconcile the unit's muster rolls with its casualty lists. Even those officers whose names were on the normal monthly muster rolls only appeared sporadically. For example, Cooke was listed on the 51st Company muster roll for November 1917, but does not reappear until he is listed on the 67th Company muster roll for November 1918.60 On 14 August 1918, the 6th Regiment published a list of the 23 Army Reserve officers who had been assigned to the regiment since 31 May. The list illustrates some of the challenges that the Marines faced in maintaining accurate records in wartime. Three of the officers listed were actually Marine Corps rather than Army officers. The 14 August roster also did not contain the names of 14 other Army officers that the master list indicates served with the regiment during the period. Most, but not all, of the officers missing from the August roster had been transferred from the 6th Regiment to stateside assignments or to other units in the 2d Division in early or mid-June.61

One of the notable names missing from the August list was Lieutenant Blythe M. Reynolds. As with many of the young men who sought commissions in 1917, the 23-year-old Reynolds's interest in military affairs predated the nation's entry into the war. He spent the summer following his 1916 graduation from Clarkson College of Technology attending the civilian military training camp at Plattsburg. Upon his graduation from the 2d OTC at Fort Niagara, New York, he arrived in France on 16 January 1918 and was assigned to the 76th Company of the 6th Regiment. Reynolds suffered a gunshot wound to his right leg during the regiment's 19 July 1918 attack on La Râperie during the Aisne-Marne offensive. In recognition of his bravery and leadership, he was awarded a Silver Star and a Croix de Guerre with palm for being cited in Army dispatches. After a long recovery from his wounds, he returned to the 6th Regiment and sailed back to the United States on 17 February 1919 with the 74th Company. As the 6th Regiment were involved in a nearly unbroken string of operations from June through August, it is perhaps understandable that Reynolds and the other officers were missing from the list.62

Another possible explanation for the absence of the Army Reserve officers from the historical narrative returns to the arguments that historian Heather Venable has made on the crafting of the Marines' "brand." Many of the primary or secondary works on the 4th Brigade in the Great War were written by Marines or those closely associated with the Corps. These authors rightly viewed the war in general, and the Battle of Belleau Wood specifically, as key events in the founding myths and lore of the Service. Simply stated, having too many Army faces in the narrative muddied the historical waters and somewhat undercut the exclusivity and exceptionality claimed by the "Marine" brigade.

When Second Lieutenant Wayne E. Perkins wrote home upon leaving the Belleau Wood battlefield on 1 July 1918, he was still 11 days shy of his 22d birthday. The 1916 graduate of the Culver Military Academy had dropped out of the University of Illinois a month after the United States entered the war to attend the 1st OTC at Fort Sheridan. After assuring them that he still retained his "good health, good looks and happy disposition," he proudly informed his parents,

Yesterday we came out of the line (not trenches) after 28 days of hell. Some day some one will tell the story as it should be told. How the Marines met the French retreating, met the Huns drunk with victory, and hurled them back. I am convinced that had it not been for the United States Marines, Paris would surely have been taken. . . . It has been an honor to serve with them.63

Although Perkins left the battle unscathed, his luck would not hold. Eighteen days after posting the letter, his left leg was shattered by a machine-gun bullet during the Allied attack to reduce the Soissons salient. He was far from being alone in his misfortune and most of the members of his platoon were killed or injured in the assault; an Army officer and his Marines united in their suffering and loss. Perkins spent the next six months recovering from his wound.64

This article is neither meant to downplay the sacrifice, valor, and accomplishments of the Marines in World War I, nor is it intended to exaggerate or to shine an unmerited light on the service of the Army Reserve officers who fought with them. However, as Perkins and the other doughboy devil dogs often paid in blood for their service with the Marines and enabled the 4th Brigade to overcome its shortages of key leaders, it is important—as Perkins noted—to "tell the story as it should be told" and add them to the unit's narrative.

•1775•

Endnotes

- The History and Achievements of the Fort Sheridan Officers’ Training Camps (Chicago, IL: Hawkins and Loomis, 1920), 124; and “The University and the War: Taps Eternal,” Alumni Quarterly and Fortnightly Notes of the University of Illinois 3, no. 49, 15 July 1918, 347–48.

- “Nashville Gives Another Son in Freedom’s Cause,” Nashville Tennessean, 28 June 1918, 1; and History and Achievements of the Fort Sheridan Officers’ Training Camps, 85.

- 2d Division, Special Orders 228, 2 September 1918, file “Army Personnel Attached to the Marines,” box 51, RG 127, entry 240, NARA. Much of the personal information used to fill in the biographical information for the soldiers involved in this study and to verify their service in the 4th Brigade comes from the U.S. Army Transportation Service passenger lists for 1910–39, draft registration cards from 1917 and 1918, Marine Corps muster rolls from 1917–18, and the federal census information from 1900, 1910, and 1920. All of these records have been digitized under a partnership between NARA and Ancestry.com and accessed via Ancestry.com. The U.S. Army Transport Service Passenger Lists report that O’Hara sailed for France on 26 July 1918 on board the SS Finland (1902) and sailed for home on 24 July 1919 on the USS Saint Paul (1895). Entry for Capt Mortimer A. O’Hara, U.S. Army Transport Service Passenger Lists, Ancestry.com.

- “U.S. Army Personnel (Including YMCA) Attached to Marine Corps Organizations,” compiled by Joel D. Thacker, Muster Roll Section, Headquarters Marine Corps, box 2, “AEF Misc File,” Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, Record Group (RG) 127, entry 240, NN3-127-97-002, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Washington, DC. Thacker also later expanded the list with revisions and more detailed information, housed in box 51, file “Army Personnel Attached to the Marines,” Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, RG 127, NN3-127-97-002, entry 240, NARA, hereafter “Master List.”

- Listings for Rubin, Washburn, Moakley, Gumm, Harris, and Hettick, “Master List.” For an example of an officer assigned only for training, see the listing on the “Master List” for Lt R. A. Bringham of the 58th Infantry, 4th Division, who was attached to the 5th Regiment for 3–7 July 1918, “Master List.” While it was the responsibility of the U.S. Navy to provide Marine units their chaplains and medical personnel, the rapid wartime expansion of the Navy and the need to replace physicians and chaplains due to wounds, leave, or schooling, often led the 2d Division to temporarily make up these shortfalls with Army officers. For example, 1stLt Herman Rubin served as the regiment surgeon for the 5th Regiment for 27 June–6 August 1918 and James I. Moakley served briefly as the chaplain of the 1st Battalion, 5th Regiment.

- Maj Edwin N. McClellan, The United States Marine Corps in the World War (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1920), 11–13, 18. This work was updated and reprinted in 2014 by Marine Corps History Division as part of the division’s World War I commemorative series.

- “Report of the Chief of Staff,” in War Department Annual Reports, 1913, vol. 1 (Washington, DC: U.S. War Department, Government Printing Office, 1913), 151–52.

- In 1915 and 1916, the Army trained approximately 20,000 civilian volunteers at Plattsburg Barracks, NY, and a handful of other locations. The civilians who attended the camps were under no obligation to join the Army and received only limited military training. The volunteers viewed their attendance as a means of raising the public’s awareness of the nation’s lack of military preparedness.

- Richard S. Faulkner, The School of Hard Knocks: Combat Leadership in the American Expeditionary Forces (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2012), 28–32, 36, 56.

- LtCol Kenneth J. Clifford, Progress and Purpose: A Developmental History of the United States Marine Corps, 1900–1970 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1973), 8–17; and Jack Shulimson, The Marine Corps’ Search for a Mission, 1880–1898 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1993), 202–10.

- Allan R. Millett, Semper Fidelis: The History of the United States Marine Corps (New York: Macmillian, 1980), 287.

- Commandant, USMC, to secretary of the Navy, memo, “Mobilization Plan-Marines,” 11 July 1916, box 389, RG 127, entry 18, NARA. A later memo to the Commandant summarized the Marines’ mobilization efforts from 1913 to 1918 and highlighted the lack of any major concern for a mass mobilization prior to the war. HQ USMC Planning Section to Commandant, memo, “Training and Preparation for War,” 15 March 1920, box 389, RG 127, entry 18, NARA.

- Maj C. H. Metcalf, “A History of the Education of Marine Officers,” Marine Corps Gazette 20, no. 2 (May 1936): 15–19, 47–48; and LtCol Charles A. Fleming, Capt Robin L. Austin, and Capt Charles A. Braley III, Quantico: Crossroads of the Marine Corps (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1978), 20–27.

- Lemuel C. Shepherd Jr., “My Memoirs, Part I of the Autobiography of Lemuel Cornick Shepherd, Jr.,” unpublished manuscript, Gen Lemuel C. Shepherd Jr, Memoirs, Boyhood–1920, Lemuel C. Shepherd Jr. Papers, VMI Archives, Lexington, VA, 14, 20–22.

- Annual Report of the Major General Commandant of the United States Marine Corps to the Secretary of the Navy for the Fiscal Year 1917 (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, Government Printing Office, 1917), 4–5.

- Annual Report of the Major General Commandant of the Marine Corps to the Secretary of the Navy for the Fiscal Year 1917, 4–5; Annual Report of the Major General Commandant of the United States Marine Corps to the Secretary of the Navy for the Fiscal Year 1918 (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, Government Printing Office, 1918), 5; and J. Michael Miller, The 4th Marine Brigade at Belleau Wood and Soissons: History and Battlefield Guide (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2020), 7.

- 5th Marines, Regimental Order 10, 14 November 1917, box 51, RG 127, entry 240, NARA.

- Commander, 4th Brigade, “Memorandum for Commanding Officer, 5th Regiment,” 15 January 1918; 6th Marines, Special Orders 70, 12 March 1918; and 2d Division, Special Orders 80, 27 March 1918, all box 51, RG 127, entry 240, NARA.

- “Lieut Leonard Is Cited for Bravery,” Boston (MA) Globe, newspaper clipping, no date, Wallace Minot Leonard Jr. file, Amherst College Alumni Collection, Amherst College Archives and Special Collections, Amherst, MA.

- Letter from “Wayne” to “Dear Folks,” 1 July 1918, box 54, file 3d Bn Replacements and Casualties, 18 June 1918, RG 120, entry NM-91 1241, NARA, College Park, MD, hereafter “Wayne” letter to “Dear Folks.” The writer noted that one of his Culver Military Academy classmates died in the fighting. This means that the writer was 2dLt Wayne Perkins, who graduated from Culver in 1916, and served with the 81st Company, 6th Machine Gun Battalion. “Life Memberships,” Minute Man: The Sons of the Revolution in the State of Illinois 14, no. 6, October 1924, 3.

- 2dLt Calvin L. Capps to Commander, 6th Marines, memo, “Transfer,” 4 March 1918; 1stLt W. A. Powers to Commander, 6th Marines, memo, “Statement,” 6 April 1918; and AEF GHQ Adjutant General to Commander I Corps, memo of 6th endorsement, 16 April 1918, all box 51, RG 127, entry 240, NARA. Capps, from Wake, NC, departed for France on 13 September 1917 and was first assigned to the 5th Regiment on 11 November 1917 and later transferred to the 6th Regiment on 17 January 1918. While serving with the 5th Regiment, Capps and Lemuel Shepherd became close friends. In the entry for 13 November 1917 of his diary, Shepherd noted that he “had grown fond of the Army Reserve officers attached to the Company.” On 7 December 1917, he recorded, “LT Capps and I have become great friends and I like him very much.” “Copy of Diary Kept by Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr. Lieutenant U.S.M.C. during World War I,” Lemuel C. Shepherd Jr. Papers, VMI Archives.

- 2dLt Herbert K. Jones to Commandant, U.S. Marine Corps, memo, “Request for Transfer into Marine Corps,” 30 June 1918, with endorsement from G. H. Osterhout on same date, box 51, RG 127, entry 240, NARA.

- The information on the arrival dates of the officers comes from the U.S. Army Transport Service Passenger Lists for 1917 and 1918, digital records of NARA, Ancestry.com. Of the officers with three months or more of service in the 4th Brigade, or who were killed or wounded prior to three months service, it was possible to find the OTC attendance of 70 of the 90 soldiers. It is not surprising that Fort Sheridan and Plattsburg Barracks provided most of the 4th Brigade’s Army officers. Unlike most of the other OTCs, neither of these posts was the site of a division mobilization. This meant that their graduates served as officer “fillers” to serve the needs of the Army.

- Faulkner, The School of Hard Knocks, 31–33, 69–71.

- Ralph Barton Perry, The Plattsburg Movement: A Chapter of America’s Participation in the World War (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1921), 190.

- Perry, The Plattsburg Movement, 202.

- The statistics on the education levels and occupations of the 90 officers comes from the records of the 1910 and 1920 Federal Census, New York Abstracts of Military Service in the World War, State National Guard and militia rolls, city business directories, and college yearbooks from the digital records of NARA, Ancestry.com. One of the best sources for occupational information was the draft cards that the officers submitted in 1917, also from the digital records of NARA, Ancestry.com. Given the number of graduates of the Fort Sheridan OTC in the group, the History and Achievements of the Fort Sheridan Officers’ Training Camps was also a key source of the officers’ biographical information. The Selective Service Act of 1917 required all males between the ages of 21 and 31 to register for the draft, this included men already attending OTCs.

- Capps, “Transfer.” Four of the nine who would serve with the 6th Machine Gun Battalion were assigned to the unit on 27 March 1918 immediately upon their graduation from II Corps machine gun schools. 2d Division, Special Orders 80, 27 March 1918, NARA.

- “Lieut Leonard Is Cited for Bravery.”

- Peter F. Owen, To the Limit of Endurance: A Battalion of Marines in the Great War (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2007), 75. This book is a well-researched and excellent account of the battalion’s experience in the war. This author only takes exception to Owen’s characterization of the Army Reserve officers.

- Clifton Cates letter, “Dear Katherine and Protho,” 22 February 1918, Clifton Cates Papers, Historical Resources Branch, Marine Corps History Division (MCHD), 3.

- Capt R. T. Zane, commanding, 79th Company, 6th Marines, “Copy of Official Record of Lieut. W. M. Leonard, Jr.,” box 51, RG 127, entry 240, NARA. Peter F. Owen is correct in stating that some of Leonard’s troops did not like the officer. In 1979, Glen H. Hill wrote a short account of his experiences at Belleau Wood in which he criticized Leonard’s leadership. Glen G. Hill letter to G. M. Neufield, head of the Reference Section, Marine Corps History and Museums Division, 17 January 1979. Hill’s criticism was not echoed by other members of the company who wrote closer to the event. In an article published in Marine’s Magazine, Romeyn P. Benjamin described Leonard smiling and smoking during the 6 June attack. Benjamin admitted that he “laughed at him” when Leonard walked between the unit’s half-platoons while smoking but also noted that it was not until he heard Leonard call “All right—2nd platoon, stick with me,” to begin the attack that Benjamin “recovered his wits” in the confusion of battle and moved forward. Romeyn P. Benjamin, “June 1918,” Marine’s Magazine, July 1919, 6–7. The author thanks Owen for providing copies of the Hill letter and the Benjamin article. Letters sent home by Sgt John P. Martin in July 1918 also contain no hint of criticism of Leonard’s leadership. In fact, in correspondence that Martin wrote to Leonard’s father after hearing of the young officer’s death, the sergeant indicates his high regard for the deceased. John P. Martin, letter, “Dear Mother and Father,” 8 July 1918; and correspondence between Martin and Wallace Leonard Sr. in 1919, John P. Martin Papers, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- Annual Report of the Major General Commandant of the United States Marine Corps to the Secretary of the Navy for the Fiscal Year 1918, 5.

- MajGen Robert Blake, USMC, Oral History Transcript, 26 March 1968 session, Benis M. Frank interviewer, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD, Quantico, VA, 1972, 3.

- On 29 June 1861, Abraham Lincoln attempted to calm MajGen Irvin McDowell’s fear that his army was too inexperienced and untrained to attack Confederate forces by noting, “You are green, it is true; but they are green, also; you are all green alike.” 63d Congress, 3d Session, Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, pt. 2 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1863), 38.

- Headquarters, 6th Marines, memo, 23 December 1917, box 51, RG 127, entry 240, NARA.

- “Report of Duties for the Month of December 1917, in Compliance with General Order N. 83, War Department, July 6, 1917,” for 1stLt Herman Allyn, 4 January 1918; 2dLt James Brewer, 4 January 1918; Benjamin Brown, 5 January 1918; and James Cooper, 5 January 1918, all box 51, RG 127, entry 240, NARA.

- “Memorandum for Captain Pearson, Assistant Adjutant, 2nd Division,” from F. E. Evans, 17 May 1918, box 51, RG 127, entry 240, NARA.

- 2d Division, Special Orders 91, 8 April 1918; Adjutant, 6th Marines, to Capt Pearson, Assistant Adjutant, 2d Division, memo, 17 May 1918, both box 51 RG 127, entry 240, NARA; and Joseph Agustin Brady, 1917 Draft Card, Ancestry.com.

- 4th Marine Brigade War Diary, 29 May 1918, in Records of the Second Division, vol. 6 (Washington, DC: U.S. Army War College, 1928).

- Commander, 55th Company, “Memorandum for Major McClellan,” undated, box 51, RG 127, entry 240, NARA (Tilghman’s name is misspelled Tillman in the text); and The History and Achievements of the Fort Sheridan Officers’ Training Camps, 159.

- Commander, 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, award recommendation for R. H. Loughborough, 31 December 1918, box 51, RG 127, entry 240, NARA.

- “Cooke, Elliot D. Capt,” personnel note card number 3, undated; “Cooke, Elliott D. National Army Attached to U.S. Marine Corps”; and Commander, 6th Marines to Commander, 2d Division, memo, “Recommendation for Promotion,” 14 November 1918, all box 51, RG 127, entry 240, NARA.

- Commander, F Company, 5th Marines, to Personnel Officer, 5th Marines, memo, “Death of Lieutenant Robert S. Heizer, USR,” 23 September 1918; and Commander, F Company, 5th Marines, to Personnel Officer, 5th Marines, memo, “Death of Lieut. Jerome L. Goldman, USR,” 23 September 1918, both box 51, RG 127, entry 240, NARA. For other examples see, Capt F. S. Kieren, Commanding Company B, 5th Marines, memo, “Death of Second Lieutenant Frazier”; and Commander, Company G 5th Marines, memo, “Epitome Lieutenant James C. Brewer, U.S.R.,” undated, both box 51, RG 127, entry 240, NARA.

- The Army Reserve officers killed at Belleau Wood were James Brewer, Harry Coppinger, Jerome Goldman, Robert Heizer, and William Peterson of the 5th Regiment and Calvin Capps, Henry Eddy, Harold Mills, and James Timothy of the 6th Regiment. Fred Becker (5th Regiment) and Herbert Jones (6th Machine Gun Battalion) were killed in the Aisne-Marne fighting, and Emmon Stockwell (6th Regiment) was killed at Saint-Mihiel.

- “Memoirs of Don V. Paradis, Former Gunnery Sergeant USMC,” in Don V. Paradis collection, Historical Resources Branch, MCHD.

- War Department Cablegram No. 704-R, 28 January 1918; AEF GHQ Special Order 92, 2 April 1918; 2d Division Special Order 92, 2 April 1918; 2d Division Special Orders 124, 4 May 1918; Commander, 6th Marines to Commander, 2d Division, memo, “Officers for Return to United States,” 17 May 1918; and Adjutant, 6th Marines, memo, 24 May 1918, all box 51, RG 127, entry 240, NARA.

- Headquarters 4th Brigade, memo, 8 June 1918, in Records of the Second Division, vol. 6.

- 2d Division Special Orders 155, 4 June 1918, box 51, RG 127, entry 240, NARA.

- Heather Venable, How the Few Became the Proud: Crafting the Marine Corps Mystique, 1874–1918 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2019), 13–15, 140–49, 196–200; and George Barnett, George Barnett, Marine Corps Commandant: A Memoir, 1877–1923, ed. Andy Barnett (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2015), 147–49.

- Commander, 6th Marines, to Commander, 2d Division, memo, “Officers for return to the United States,” 17 May 1918; and “Memorandum for Captain Pearson, Assistant Adjutant, 2nd Division,” from E. E. Evans, 17 May 1918, both box 51, RG 127, entry 240, NARA.

- BGen A. W. Catlin, With the Help of God and a Few Marines (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page, 1919), 5–14, 18, 24–25, 159. Throughout the work, Catlin is unrelenting in his pride and boosterism of the Marine Corps. As with Barnett, he was driven to ensure the long-term survival of the Corps and as such consistently set out to demonstrate the superiority of the Corps’ personnel, training, and performance during the war. It is not much of a stretch to argue that his desire to preserve the Corps colored his views on the Army Reserve officers. He mentioned them only six times in the book, with three of those cases being in his roll-up of this regiment’s citations. The kindest thing he noted of the Army officers was, “They became practically Marines in short order, some of them being killed or wounded in the subsequent fighting.” Catlin, With the Help of God and a Few Marines, 29.