The Hostages’ View

The night the revolt broke out, the Morrises and a dozen other hostages, including two European women and a Peace Corps officer, were captured and incarcerated in Limbang, while four Sarawak constabulary officers were killed during the attack.7 Dorothy Morris provides a vivid description of events from the hostages’ point of view.8 She wrote that, even though they had some warning, the revolt came as a complete surprise when they were suddenly ambushed in their own compound on the night of 8 December and led down in the dark to the dense jungle just above a small stream with very steep banks. The hostages sat there with every form of biting nightlife assailing them, Morris clad only in his underpants without much seat in them and the inevitable perished elastic band at the top and no safety pins. In the short time available, he had not been able to locate any more dignified clothing, though his wife had been able to dress more adequately, including a pair of heavy shoes. Morris was savagely bound with nylon fishing cord, but his wife’s hands were left free. Two decidedly question-able bandits sat on either side of her clutching an arm, while another pointed a kris (a Malay dagger with a wavy blade) unpleasantly close to Morris’ back. After an hour, they were ordered up the slope to a clearing above the residency, when Dorothy Morris lost her footing and slid down to the bottom, earning bruises from hip to shin. Suddenly, large numbers of rebels, all looking scruffy and intent despite a mix of uniforms and weapons, filed past them. Some stopped and stared with no noticeable reaction to the scene, and one, whose aim was fortunately very poor, attempted to spit in her face.9

Richard and Dorothy Morris, the resident and his wife, who were both taken hostage, pictured in 1954 with members of the Sarawak Constabulary at Kanowit, seven years before the rebellion. Morris was working with the police force at the time, which was in the process of being developed.

Photo courtesy of Eileen Chanin

Shortly afterward, the Morrises were moved to the jail, where they found Police Inspectors Abang Zain bin Abang Latif and Latif bin Basah, with King Shih Fan, a Public Works Department engineer, and three other policemen. Inspector Latif had been wounded at some point. Morris, still clad only in his underpants, was used as a human shield on the way up to the police station. Later that day, the Morrises were allowed back to the residency to collect some clothes and belongings. The following afternoon, their spirits rose considerably when the hastily reconstituted Limbang Red Cross led by Inche Omar bin Sanauddin, a re- tired postmaster, and the wife of the Public Works Department superintendent, appeared with coffee, rice, towels, codeine, bandages, and ointment for the wounded police inspector in the next cell. Dorothy Morris recalls that these tireless, brave, and devoted few did more than they will ever know for the comfort of those behind bars. She recalled that one of the most unsettling aspects of their incarceration was the distasteful business of being glared at by their guards through the bars of their only window. In the meantime, three Catholic priests and a member of the United States Peace Corps—18 year-old Fritz Klattenhoff—were detained in the police station along with another member of the Public Works Department.10

By 10 December, the tougher, more dedicated rebel elements had been dispatched to the outskirts upriver as rumors spread that the Dyaks (loyal aboriginal Sarawak headhunters) were coming down to “do over” the rebels. That night, Dorothy heard whispered discussions in Malay between the guards sitting at the top of the steps just outside the cell door. Although she only heard snatches, there was frequent mention of “prisoners,” “sunrise,” and “shooting.”

Dorothy Morris would later state that she will never know, nor does she want to know now, whether it was her over-taxed imagination or wishful thinking on behalf of the guards, but she prayed she and her husband would be given courage to face whatever lay ahead, and then prayed again for her children so many hundreds of miles away in Australia.11

On 11 December, there was a change in the attitude of their guards, who took every opportunity to whisper to them that their hearts were not really in the enterprise and they hoped the “Tuan” resident would deal gently with them when it was all over. Though the Morrises were not aware of it at the time, the military chief of the rebels, Yassin Affandy, had passed through Limbang on his way to Temburoung District and realized quickly that his cause was lost in the shadow of coming British forces.12 The feeling that something was about to happen was further strengthened when friendly visitors conveyed news of British military successes in Brunei Town, Kuala Belait, Seria, and Miri. That day, most of the hostages were moved to the hospital. In spite of the change in conditions, the hostages did not get much sleep that night, with the significant increase in guards and noise. They must have sensed something was about to happen. At first light the next morning, Dorothy Morris writes,

We didn’t enjoy the bangs and the flying glass one bit, but I do well remember the glorious sound . . . calling on the rebels to surrender . . . during which we sang our little ditty about “Green Bonnets.”13

The hostages’ identities were quickly established, and then they heard Sergeant Dennis Smith’s reassuring voice saying, “Come on out, old girl.” When the Morrises emerged through the rather jagged aperture of the broken window, Richard Morris recalls,

It was 0620 when we climbed out of the window. The last eighteen minutes were now part of history, minor history maybe, but terribly important to all those who had played a part in its making. The fire-fight was over, but there was still quite a lot of shooting and the occasional crump of a grenade at the beach\head was extended.14

The hostages did not waste time with pleasantries but quickly moved into the hospital ward where the other hostages had been held. They were all present and correct, if a trifle dazed. With plenty to do in preparing beds and bandages for the wounded, Dorothy found it difficult to believe that the worst was over. She later wrote, “Any sense of joy was tempered for all of us to one of quiet thankfulness mixed with great sadness and the consciousness of a debt we could never repay, by the presence of the dead and wounded around us.”15

The Military Response

As news of these events filtered through to Singa- pore, two companies from the Royal Gurkha Rifles on standby were moved to the Royal Air Force (RAF) stations in Singapore at RAF Changi and RAF Seletar to fly to Labuan, a small island off the coast of Brunei.16 Some flights were diverted to Brunei Town airfield when it became clear the North Kalimantan National Army (TNKU) rebels had failed to seize control of the capital. This TNKU militia had been supplied by Indonesia and was linked to the Brunei People’s Party, which favored a North Borneo Federation. Landing late in the evening of 8 December, the Gurkhas advanced immediately toward Brunei Town and engaged in a series of actions that resulted in six casualties, including two dead. The Gurkhas met such fierce resistance when they moved toward Seria that they were forced to return to Brunei Town to counter the ongoing rebel threat there and near the airfield until reinforcement arrived.17

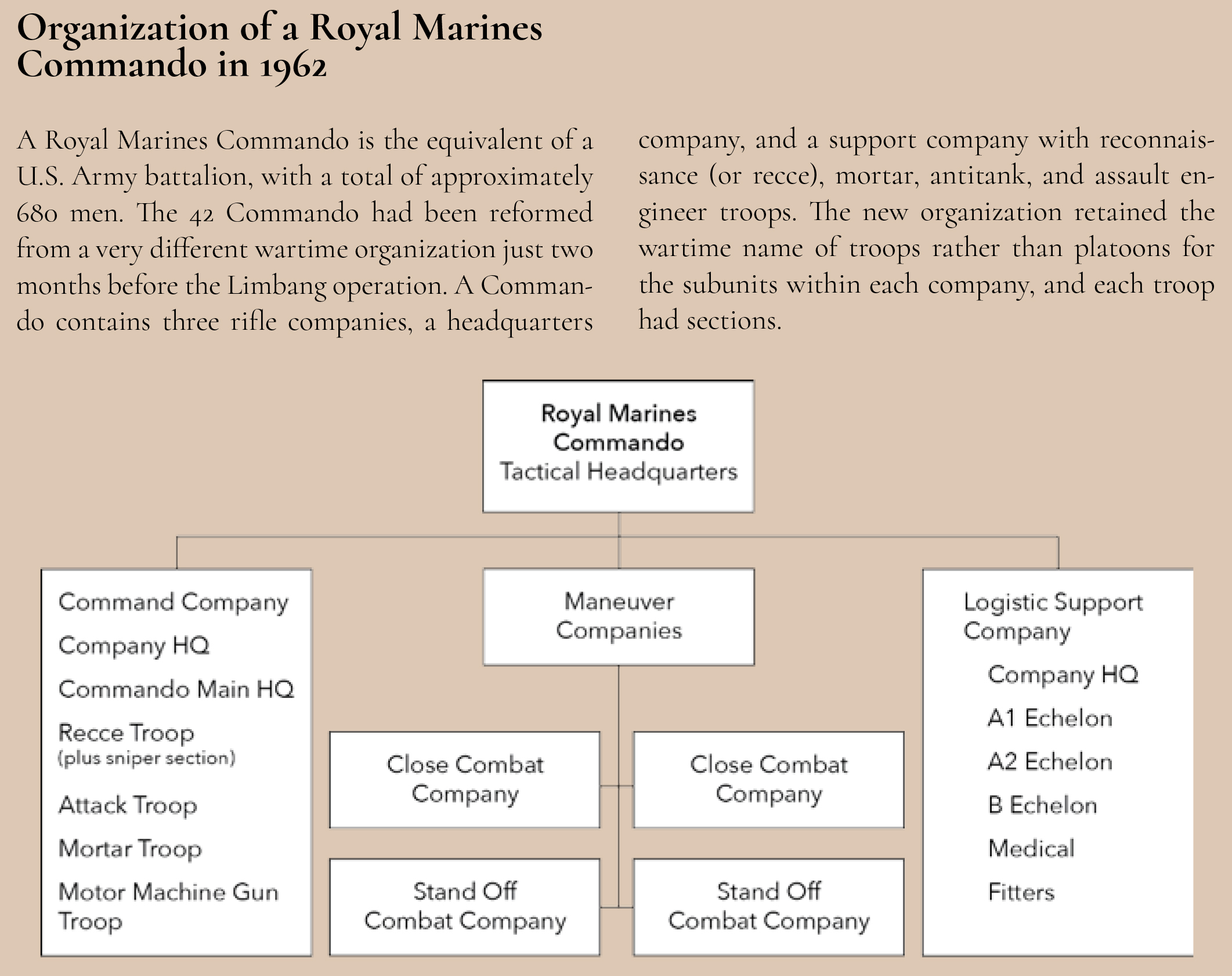

Additional British forces available to react to the rebellion were stationed in Singapore. Those selected to offer further support to the situation confronting the Gurkha Infantry Brigade, who had already restored order in Brunei, were the Royal Marines of 42 Commando.18 The 3d Commando Brigade, Royal Marines, at this time consisted of 42 Commando, who had been looking forward to Christmas in Singapore after an extremely busy year of exercises, and 40 Commando, who were embarked on HMS Albion (R 07) off Mombasa, Kenya. Brigade headquarters had only recently returned from controlling exercises in the Aden Protectorate in southern Arabia, while 45 Commando were under independent operational command and on active service in Aden. On 8 December, 42 Commando was put at short notice to move to Brunei, and two days later they were on their way. Their Commando Headquarters and Company L flew first into Labuan and then into Brunei Town, where the Gurkha Rifles had already restored order.

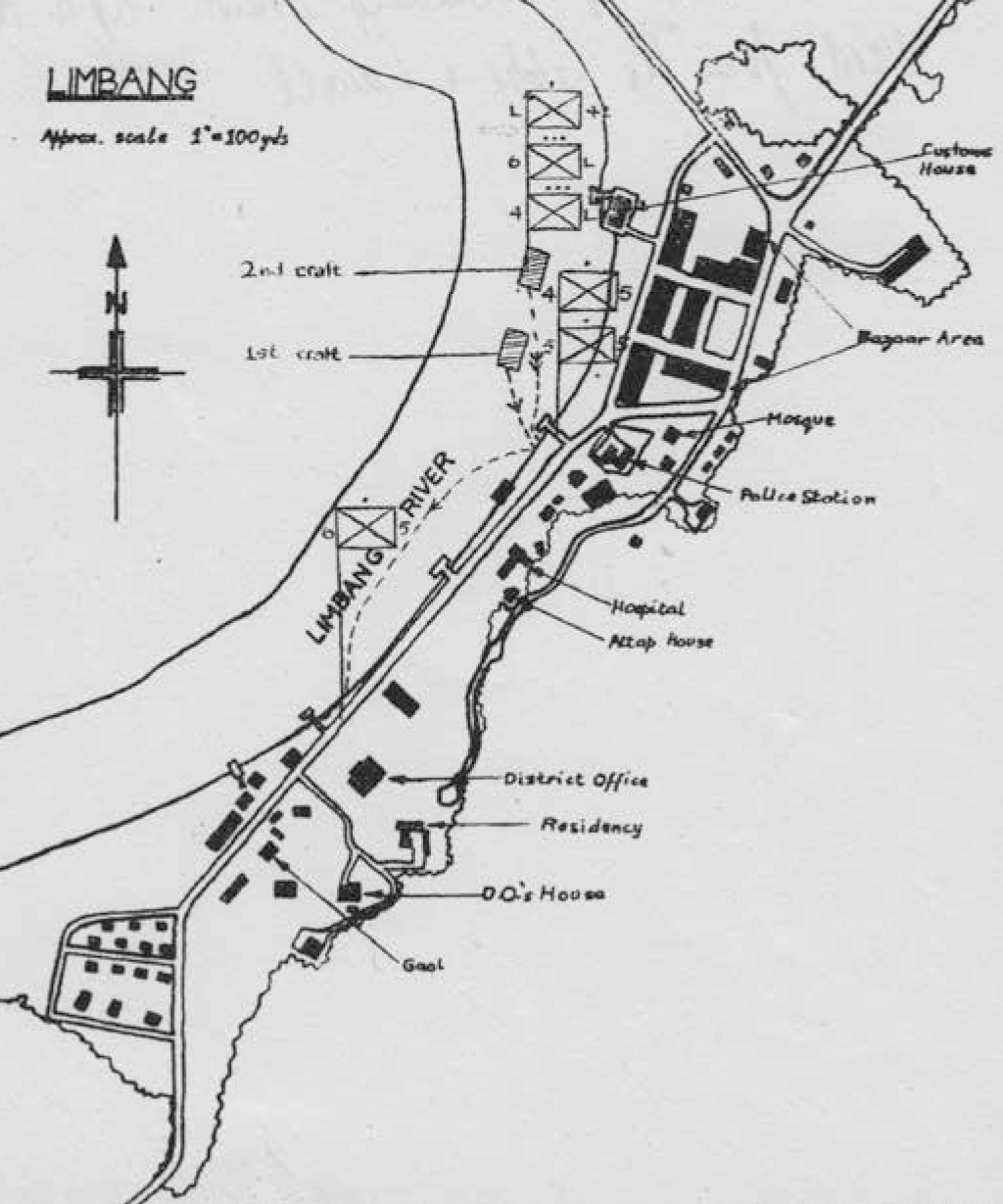

Sketch of Limbang, showing the positions of the jail, hospital, police station, and residency, where hostages were being held by the rebels.

Map by author

At 0600 on 11 December 1962, Brigadier A. G. Patterson, OBE, MC, commander of 99 Gurkha Infantry Brigade and now in command of operations against the Indonesian terrorists, greeted the newly arrived company commander of Company L, 42 Commando Royal Marines, Captain Jeremy Moore, who had earned a Military Cross in the Malayan jungle 10 years earlier. Perched on the hood of his vehicle, the brigadier made his directive quite clear: “Your Company will rescue the hostages at Limbang.”

During the next 24 hours, one of the most audacious amphibious raids in post-war Commando his- tory was planned and executed, turning the whole course of the Borneo campaign. At that time, only 56 men of Company L had reached Brunei, plus a section of Vickers .303-inch medium machine gunners; however, with a few other additions, the final number on the raid totaled 89. Intelligence was scarce but they believed that about a dozen hostages were being held in Limbang, including Resident Richard Morris and his wife, Dorothy, another woman, and U.S. Peace Corps Officer Fritz Klattenhoff.

As Captain Moore, his second in command, Lieutenant Peter Waters, and his company sergeant major, Quartermaster Sergeant Cyril Scoins, took stock of the situation, the Marines prepared for the ordeal to come. Approximately three hours later, the commanding officer of 42 Commando, Lieutenant Colonel Robin Bridges, and his intelligence officer, Lieutenant Ian Walden, arrived to take over the difficult responsibility of obtaining information and intelligence for the operation. They managed to fly over Limbang, but their view was obscured by low cloud cover and they achieved little toward the situation on the ground. It was clear in everyone’s mind that speed and surprise were essential. The decision was soon made that the raid would have to take place at dawn the following morning. Of prime importance was the need to find some rivercraft in which to mount the operation. Lieutenant J. P. Davis, some newly arrived naval ranks, and the author set about this task, inspecting the myriad small boats along the Brunei waterfront. There were hundreds of them, but none were particularly suitable for transporting 100 men upriver for 12 miles and then carrying out a possible frontal assault against an unknown enemy. Just as they reached the north end of the extensive waterfront, they came across two old Z-craft belonging to the Brunei government that appeared to be in working order.19 While there were no signs of any crew, one of them had on board two yellow bulldozers, which apparently were used to push the craft off the mud when they got stuck. Nevertheless, the two craft suited the Commando purpose admirably and the bulldozers went on the raid.

Just after midday, two coastal minesweepers, the HMS Fiskerton and HMS Chawton, sailed into the harbor, subsequently providing the only reliable communications between Brunei and Singapore. They had been piloted downriver by Captain Erskine Muton, the local director of the Brunei State Marine Department. The Royal Navy immediately took command of the situation, providing their two first lieutenants to command the Z-craft and engine room staff to ensure they were both in working order.

The minesweeper captains, Lieutenant Harry Mucklow, RN, and Lieutenant Jeremy Black, RN, came ashore and, with Captain Moore, helped in the detailed planning. This was the first meeting between Moore and Black who, 20 years later, would find themselves in action together again in the South Atlantic when Moore was the force commander and Black was the captain of the aircraft carrier HMS Invincible (R 05) during the Falklands campaign. By late afternoon, the engines and maneuvering ability of both craft had been thoroughly checked by the seamen and engineers, and were pronounced fit for their task. The only protection for those embarked were large backpacks acting as sandbags, a few earth-filled oil drums and the crafts’ own 1.5-inch wooden planking.

Meanwhile, Moore was collecting as much intelligence as possible, but he found that he had no more than small-scale maps and one out-of-date aerial photograph to help him. He knew that a small police launch that had approached Limbang two days earlier had been driven off by heavy small-arms fire. The strength of the enemy and his dispositions were virtually unknown, as estimates varied from 30 to more than 100, but it was obvious that the rebels were there in some numbers and that they had captured police weapons to add to their own. However, Moore assessed that their firepower would be fairly ineffective beyond 100 yards, and at close quarters, the two sides would be about equal. He knew that his highly trained Marines would therefore be more than a match against what appeared to be a poorly led enemy.

The only aerial photograph of Limbang, which was taken in 1959, that was available to brief the attacking force.

Photo by author

Royal Marines Commandos embarking before the raid. These backpacks were used partly as protection from enemy fire.

Photo by author

Moore anticipated that he might be able, by a show of force, to bluff the rebels into surrendering. If that failed, or if the operation was prolonged, the rebels would either shoot the hostages out of hand or threaten to do so to force him to withdraw. His prime concern was the safety of the hostages, but he did not know where they were being held. Several possible locations presented themselves—the police station, the jail, the hospital, and the British residency—which were all separated by about 300 yards. Moore decided that the police station, almost in the center, was the most likely place for the rebels to set up their headquarters. He planned to eliminate this location before they had a chance to harm the hostages. His simple plan was to overwhelm their positions as fast as possible, each Marine withholding fire until the rebels opened up. He intended to call on the enemy to sur- render in the hope that, by a brave show of force, he could bluff his way in.

That afternoon, ammunition and equipment were checked, the Vickers .303-inch medium machine guns were mounted forward on the Z-craft where they would be most effective, while food and rest were hastily taken during what was left of the day. To ar- rive off Limbang at dawn, they set sail about midnight, guided by Captain Muton, who had earlier led the minesweepers down the river to Brunei Town. Muton admitted that he had never sailed that part of the Limbang River before. HMS Chawton’s Lieutenant David Willis, RN, cast off the leading craft at 1203 on 12 December. He was aided considerably by a clear night and a nearly full moon. The Commandos’ route lay along a series of complicated winding channels be- tween 30 and 100 yards wide flanked by the dangerous nipa swamp.20 The Royal Marines on board, already exhausted from nearly two days without proper sleep since leaving Singapore, snatched whatever rest they could, but the excitement and anticipation allowed them little rest.

The two craft, keeping just within visual distance, slowly edged their way down the narrow channels as silently as they could, no lights or noise emanating from those on deck, leaving only the grinding engines to announce their presence to any waiting ambushers. After half an hour, the leading craft slewed across the river as one of its engines failed, but was soon fixed. Occasionally, in the narrower passages, the craft bumped perilously against the mangrove roots. By 0200, both craft reached the main Limbang River, approximately five miles from the town, where they remained hidden in the shadows of the jungle edges until 0430. This was a frustratingly anxious time for the Marine Commandos. Some lay awake contemplating the inevitable battle ahead, wondering what their first taste of action would be like; others fitfully slept with their weapons in their hands. The mangrove branches hid the bright moon casting shadows above them, allowing imaginations to conjure up alarming configurations.

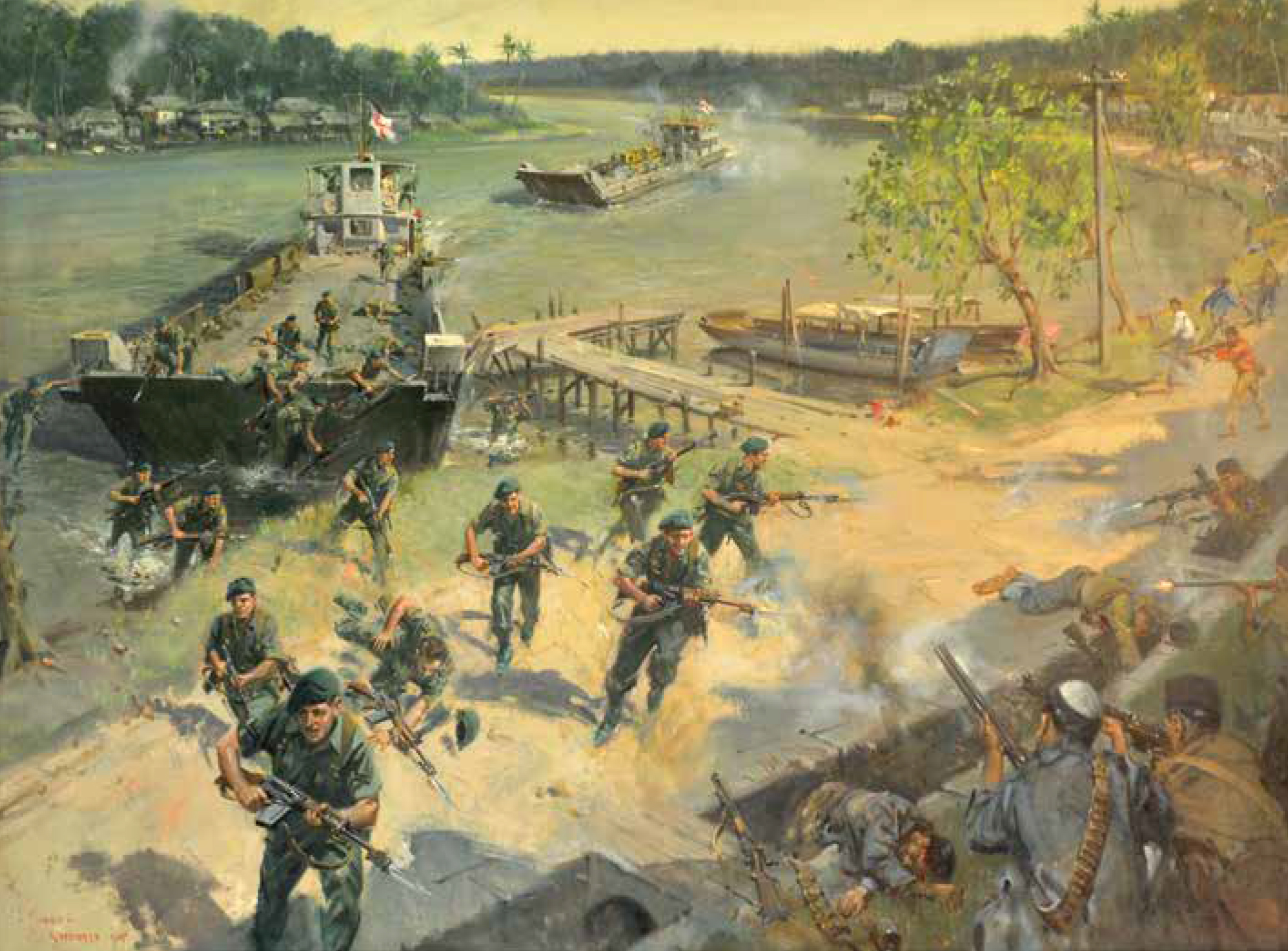

Many of the dozing Marines were nudged awake as the engines started up again at 0430, and the two craft nosed their way into the much wider Limbang River, leaving the passengers feeling naked and exposed in the fading moonlight. Last minute checks were made as the craft rounded the final bend toward the small town. They saw the dim lights of the town in the distance. Ever more slowly, the two craft drew nearer, and then to the surprise of everyone on board, the lights in the town suddenly went out. They would later learn that it was the routine as dawn approached. As silently as their engines allowed, and with about 50 yards between them, the leading craft came level with the northern edge of the town. Captain Moore, with his Malay-speaking intelligence sergeant, David Smith, alongside peered into the ever-lightening distance. At 300 yards, they saw movement everywhere as Limbang grew nearer. The bazaar area seemed alive, and they could just make out the police station. “Full ahead” was ordered, and the leading craft surged toward the bank. Moore turned to Sergeant Smith, who through his loudspeaker informed the enemy that the rebellion was over and that they should lay down their arms and surrender. At this, a hail of bullets greeted the approaching Royal Marines. The response from each craft was instantaneous, and by the time the leading craft had beached about 30 yards from the police station about 20 seconds later, it was clear that Company L had the fire initiative thanks largely to the heavy weight of lead pouring from the Vickers medium machine guns.

Moore recalled, We drove our landing craft straight at the bank, opposite the police station, with the second craft with the Vickers in support. . . . [T]he enemy had light machine guns, lots of rifles and shotguns, so the fire was heavy and a number of people were hit.

Two Marines of the leading troop were killed even before they got to the bank, and Lieutenant Peter Waters was hit in the leg as he jumped ashore. The coxswain of the leading craft also was hit, as were Lieutenant Davis and a seaman in the second craft still standing off and giving covering fire.21 Number 5 Troop stormed ashore, clearing the police station in its stride, with Corporal Bill Lester taking his section across the road, mopping up, and providing a cut off to the rear. Sergeant John Bickford, a Corps footballer and physical training instructor, and his section commander, Corporal Bob Rawlinson, pressed home the attack, though Rawlinson had been wounded in the back.

Meanwhile, with the coxswain wounded, the leading craft had drifted off the bank, but Lieutenant David Willis immediately took the wheel and drove the craft back into the bank. Being very unwieldy, he beached it halfway between the residency and the hospital, approximately 150 yards from the initial landing. Captain Moore reassessed the situation and ordered his troop sergeant, Sergeant Wally Macfarlane, ashore with the reserve section. Sergeant Smith, having decided that his loudspeaker was no longer a suitable weapon, accompanied them. By this time, only sporadic fire could be heard, and Sergeant Macfarlane moved stealthily north, clearing the enemy from the jungle edges that came right down to the bank in places. They reached the hospital without incident, where Macfarlane decided to press on to join up with the initial landing force near the police station. Suddenly, a group of determined enemy opened fire, killing the troop sergeant and two Marines.

Royal Marines of Company L, 42 Commando, with their two converted Z-craft, attacking Limbang against strong opposition.

Painting by Terence Cuneo, courtesy of the Cuneo Trust and Royal Marines Museum

Through the sounds of battle, Sergeant Smith heard inharmonious singing coming from within the hospital. Recognizing the tune as a version of “Coming Round the Mountain,” he called out to them in English and was able to identify the Morrises, along with several other hostages, who were unharmed but severely shocked. Their guards had fled. Captain Moore, his main task of freeing this group of hostages achieved, checked with Richard Morris to ensure that there were no more held in other locations. As he did so, one remaining rebel loosed a round from his shotgun, fortunately quite inaccurately, before disappearing into the close jungle.

During this time, the second craft had been maneuvering in the fast-flowing river to give the best supporting fire possible. The company sergeant major had taken command of the situation when Lieutenant Davis was severely wounded. At this juncture, the reserve sections on the second craft came ashore before the craft once again took up a position midstream, covering any eventuality with its medium machine guns.22

A number of the rebels were soon routed by Number 5 Troop in the area of an attap house, while Number 6 Troop cleared the police station and Number 4 Troop moved north past the mosque to the back of the bazaar, where one of the rebels engaged them from a room full of women and children.23 He was soon dislodged with no further casualties. From this time onward, most of the enemy resistance had collapsed, although a number of dissidents held out in town and the surrounding jungle. As a result, considerable movement and sniping continued during the next 24 hours.24

As soon as the second craft beached, Royal Navy Sick Berth Attendant Terry Clarke made his way to the hospital and set up a dressing station, treating the casualties while the released hostages helped him to prepare dressings. Ironically, four of the six cases of gunshot wounds were in the legs, though additional casualties would come in later as a result of men falling through the roofs of buildings during searches. Sergeant Smith set about interrogating the hostages and other prisoners, discovering that others were still being held in the jail and the southern area of Lim- bang. By late afternoon, this area also had been systematically cleared and a total of 14 hostages had been rescued unharmed.25

Later in the morning, the Z-craft returned to Brunei, this time rather more quickly and triumphantly, bringing the hostages and the casualties with them. Company L had lost five dead and five wounded, plus one sailor wounded. The police had lost six men. The wounded were quickly flown to Labuan, Malaysia, and then evacuated to Singapore. As Dorothy Morris came ashore, relief showing in her taut face, she handed the author two letters for her children—Geraldine and Adrian—safe at school in Australia. Originally, they were due to arrive in Limbang any day that week for the Christmas holidays.

That afternoon, the author accompanied Brigadier A. G. Patterson, the commander of 99th Gurkha Infantry Brigade, down to Limbang by boat to assess the situation. They met Richard Morris for the first time, along with Jeremy Moore, who gave them a firsthand account of the action. It was clear that the training, professionalism, and bravery of the Royal Marines had won the day.

As Company L consolidated during the next few days, 15 rebel bodies were found and approximately 50 prisoners were taken. It was later learned that many others died of wounds in the jungle. Of the nearly 350 rebels who had held Limbang initially, many later simply discarded their uniforms and melted anonymously into the bazaar areas of the town. Much later, Captain Jeremy Moore made the following observations:

It is perhaps interesting to note that, though my assessment of where the enemy headquarters might be was right, I was quite wrong about the hostages. Furthermore, it was chance that the second beaching happened where it did, that resulted in us taking the hospital from the direction we did. It could be that this saved us heavier casualties, though I assess the most important factor in the success of the operation was first class leadership by junior NCOs. Their section battle craft was a joy to watch, and the credit for this belongs to the Troop and Section commanders.26

Aftermath

Though the actions in Brunei lasted only a few days, there is no doubt that they acted as a catalyst for what followed.27 They kick-started a four-year jungle campaign that became known as Confrontation, a term coined by the Indonesians.28 This covered three phases starting in April 1963 and ending in August 1966, when General Suharto replaced General Sukarno as president of Indonesia in a coup and the end of Confrontation was ratified.29 During this campaign, there was considerable cross-border activity by both sides deep in the jungles of Borneo; this was indeed a junior leader’s war.

Leading Z-craft approaching the jetty after returning from the raid.

Photo by author

U.S. Peace Corps Officer Fritz Klattenhoff (center with hands on hips), who was one of the hostages, returns with casualties to Brunei on the second Z-craft.

Photo by author

Casualties arriving back in Brunei Town lying on the Z-craft before be- ing evacuated by air to Singapore.

Photo by author

Although several British infantry battalions served in Borneo, the brunt of the campaign was born by the eight Gurkha battalions and 40 and 42 Royal Marines Commandos. Between December 1962 and September 1966, there was almost always one Royal Marines Commando group in Borneo, and on more than one occasion, both were present.30 This was indeed a case of the Royal Marines being “first in, last out.”31

For the action at Limbang, Captain Moore was awarded a bar to his Military Cross; Corporals Rawlinson and Lester were awarded Military Medals; Lieutenant David Willis, RN, received a Distinguished Service Cross; and Sick Berth Attendant Terry Clarke received a commendation. Richard Morris would later receive the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (OBE).

• 1775 •

Endnotes

*The story of the daring assault on 12 December 1962 by Company L, 42 Commando, on Limbang, Sarawak, Malaysia, to rescue 14 hostages held by Indonesian rebels was supported by officers and ratings from the Royal Navy minesweepers HMS Fiskerton (M 1206) and HMS Chawton (M 1209). This article is based on the operational reports written at the time by Capt Jeremy Moore (MC), Royal Marines (RM), and LtCol E. Robin Bridges, Order of the British Empire (OBE), RM. The personal accounts included have been supplemented by those of the author and edited to include new material. Oakley served in the Royal Marines for 42 years. After service at sea, he saw active service in Malaya (1949), Port Said (1956), Northern Ireland (1957), Brunei (1962), and Borneo (1963). He later became editor of the Royal Marines journal The Globe & Laurel, and in retirement, he is now vice president of the Royal Marines Historical Society. He won the 1983 U.S. Marine Corps Historical Foundation award for his coverage of the Falklands Campaign. Editorial note: the terms and spellings used are U.S. English equivalents for military terminology.