Marine Corps University Communications Style Guide

CHAPTER SIX: DEVELOPING A RESEARCH QUESTION, WRITING A LITERATURE REVIEW, AND ORGANIZING RESEARCH

Most research papers begin with the identification of a specific problem. It is helpful to frame this problem in the form of a question, which is commonly referred to as a research question. The answer to this research question will become your thesis statement—something you may not arrive at until you are well into the process of conducting your research. This chapter covers the following topics: reviewing the literature on your topic, writing a literature review, evaluating your sources, varying your sources, conducting primary research, organizing research data, and connecting that data to your research question.

Developing a research question is the first step in narrowing your topic; it helps you focus on one particular aspect of the subject because it allows you the flexibility to test out various hypotheses as you gather data and develop expertise on the topic. The research question may help you think about the key words you will need to find information that is relevant to your topic. For example, rather than researching “counterinsurgency” or “socialized medicine”—topics that are simply too broad and may not yield a fruitful search—your search will be significantly more productive if you develop a specific research question like the one below.

Primary research question: How was the British military’s counterinsurgency strategy in Malaya different from the French military’s counterinsurgency strategy?

Subquestion 1: What were the effects of these two strategies?

Subquestion 2: What aspects of the strategies might be relevant to current U.S. military operations?

Below are a few examples of research questions you can use to direct and narrow the focus of a research paper.

1. What have current U.S. operations against Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS)/Islamic State (IS)/Daesh looked like? What effect have U.S. operations had on the current fight against ISIS/IS/Daesh since 2012?

2. What technological tools can the Marine Corps take advantage of to counter China’s growing cyber threat capability?

You are likely to develop subquestions that will help you answer your main research question and envision the scope of the paper. Below are a few examples.

1. Is China’s growing influence dangerous to the United States’ economic and security interests in the Asia Pacific region?

a. What are China’s primary interests in the Asia Pacific region?

b. How should the United States address China’s growing influence in the Asia Pacific region?

2. Should Americans view Edward Snowden as a patriot?

a. What is patriotism?

b. Did Snowden’s actions exemplify American conceptions of patriotism?

CSG 6.1 Reviewing the Literature on Your Topic

After you have collected some background information and as you begin to develop a research question, you will need to conduct a preliminary literature review. A literature review is a thorough examination of collected, published research relevant to a research question. The literature review has several main purposes, which are explained below.

1. It helps you establish a picture of the current knowledge about the topic as well as current ways of viewing or evaluating the topic.

2. It determines whether there is enough research to support your topic or to answer your research question.

3. It allows you to make sure that each source serves your purpose before you begin taking notes or analyzing the information, and that your sources are credible and unbiased.

4. It provides you with the opportunity to develop your research question and the thesis statement that will answer it within the context of the scholarly research that has already been published on the subject.

By examining the research others have done, you will gain a deeper, broader, and more contextualized understanding of your topic. Even if a source does not directly support your argument or claim, it may provide information that will help you construct an overview of your topic. Understanding other viewpoints and conflicting theories will give you a deeper perspective, as doing so gives your paper more credibility and demonstrates to your readers that you understand the full scope of the issue. As much as you may want your research to support your point of view, it is important to keep opposing points of view in mind. This will help you avoid making hasty, unfounded conclusions. When conducting a literature review, ask yourself the following questions:

1. What is known about the topic?

2. Is there a chronology attached to the topic?

3. Are there any gaps in knowledge about the subject?

4. Is there debate or consensus on some aspect of the subject?

5. What implications or suggestions for future research do the authors offer?

Here is an example of a literature review process: you are beginning a research paper on the topic of counterinsurgency (COIN). An excellent way to begin is to find an influential work on the topic and study that work’s bibliography to ascertain what that author used in preparing his or her fundamental work. This approach makes it easier to trace information relevant to your topic. In this case, we know David Galula and David Kilcullen have written several seminal works on counterinsurgency. Therefore, going online to the Small Wars Journal Reference Library, you may look directly under the topic “counterinsurgency” for an annotated list of seminal works on this subject by the authors. In each document, you will find the bibliography and notes that will guide you further in your search.

If your initial searches seem to yield few results, you may need to broaden your topic or even select a new one. Focus on your question, take thorough notes, and use a systematic approach. When in doubt, consult your institution’s reference librarians. They can assist you with finding the best key words for your search, and they may have access to databases that you do not. Reference librarians can instruct you on the use of online databases in your article searches.

CSG 6.2 Writing a Literature Review

A literature review is a synthesized discussion of other authors’ work within a particular subject area. That is, the literature review gives the reader a sense of what has already been written about the topic, the different methods researchers have used to investigate the topic in the past, the prevailing schools of thought that inform the topic, and gaps in the existing literature on your topic. Typically, your research question will guide your literature review.

Recent updates to CSC’s MMS program have required students to write an independent literature review as a component of the MMS project. The intent behind this assignment is not to create additional work but rather to encourage students to think deeply about the connections between what other sources say about their topic. This section provides some general guidance about what a literature review looks like and how to incorporate a literature review into your research paper. If you are a CSC student writing a literature review to fulfill one of your MMS milestones, consult your MMS writing guide for CSC-specific expectations for literature reviews.

CSG 6.2.1 Purpose of Literature Reviews

A literature review may serve a variety of purposes, but it will be driven by the underlying aim of your research.

If you are writing about a frequently studied and researched topic, the purpose of the literature review might be to show how your research relates to what others have already written about your topic. What will your work add to the current body of literature? Which authors, researchers, and theorists do you agree with? Which authors, researchers, and theorists do you oppose?

If you are writing about a relatively new topic, the literature review may allow you to synthesize the small body of research that does exist on your topic and to connect your claims to existing theories and methods.

If you are conducting qualitative or quantitative research, a literature review may serve to evaluate the research methods used in previous studies that have been conducted on your topic. For instance, you may choose to model a method used in a frequently cited seminal work. Conversely, you might debunk claims previous researchers have made if those claims are based on unreliable, flawed, or biased research methods.

If you are attempting to fill a gap in current research, you will want to include a research methods section to inform your reader about the status of the research that has been conducted on your topic up to this point.

CSG 6.2.2 Structure and Organization of Literature Reviews

While all literature reviews will involve some degree of summary since they require you to report on the findings of other researchers and writers, the primary purpose of a graduate-level literature review is to synthesize information from other sources. That is, you will discuss how the sources relate to one another within the context of your own research question. You may draw some overall conclusions about the status of the research on your topic.

Literature reviews are often organized by theme. This means that the literature review will discuss how each theme or subtopic is covered in a variety of sources on your topic. The literature review might also be arranged chronologically, particularly if there have been significant developments within your field of study over the years. In a literature review, a writer will often describe the merits of a particular source while summarizing the author’s findings. For instance, you may comment on whether a particular claim has merit and whether it has been challenged by others in the field. If you have included quantitative and qualitative studies in your research, you might consider comparing the methodologies researchers have used to come to their conclusions.

The length of your literature review will vary depending on the length and type of paper you are writing.

CSG 6.2.3 Literature Review Invention Strategies

The steps in writing a literature review are similar to the steps in writing a research paper. You will need to organize your ideas (invention), write your ideas (drafting), and revise your ideas (revision). Below are a few steps you might take before you begin drafting.

Make a table. Organize the table in terms of trends and themes; place each article in the appropriate section. See table 6 for an example.

Make a timeline. Organize articles from oldest to most recent. Be sure to emphasize major shifts in trends, themes, and policies when organizing information chronologically.

Put your research away when summarizing articles. Put the text in your own words. Compare what you have written with the original text to ensure accuracy.

Table 6. Literature review: theories of creativity development

|

|

Theme 1: Creativity can be cultivated

|

Theme 2: Creativity is innate

|

|

Theorist/

author

|

J. P. Guilford, “Creativity,” American Psychologist 5 (1950) 444–54, http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0063487.

A. J. Cropley, Creativity in Education and Learning: A Guide for Teachers and Educators (New York: Routledge, 2001).

R. A. Beghetto and J. C. Kaufman, “Toward a Broader Conception of Creativity: A Case for ‘Mini-c’ Creativity,” Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 1, no. 2 (2007): 73–79, https://doi.org/10.1037/1931-3896.1.2.73.

Learning and Collective Creativity: Activity-theoretical and Sociocultural Studies, eds. Annalisa Sannino and Viv Ellis (New York: Routledge, 2009).

Richard E. Mayer and Merlin C. Wittrock, “Problem Solving,” in Handbook of Educational Psychology, ed. Patricia A. Alexander and Philip H. Winne (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2009), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203874790.ch13.

|

Nancy R. Smith, “Development and Creativity in American Art Education: A Critique,” High School Journal 63, no. 8 (1980): 348–52.

|

CSG 6.2.4 Literature Review Drafting Strategies: Structure of a Literature Review

Like an essay or a research paper, a literature review will typically include an introduction, body, and conclusion. Below is a description of the

elements you might want to address in each component of the literature review.

The introduction should provide some basic context for your topic. What are the parameters of the topic (e.g., a specific time period; a particular subset of the topic)? The introduction might discuss landmark studies or present some of the main perspectives on your topic. Finally, the introduction might end with a thesis statement that addresses central themes throughout the literature or that places your stance on the topic in the context of what previous researchers have found.

The body of the literature review discusses sources using a clear organizational framework. It should synthesize common points of view and highlight points of disagreement. Below are a few methods you might use to organize your ideas in the body of the literature review.

1. History (chronological): this method is most useful when showing how perspectives on the topic have evolved over time.

Example: literature review of evolving attitudes on women in the infantry

2. Trend: this method is most useful when looking at cause and effect relationships.

Example: literature review examining the effects of the 2007–8 troop surge in Iraq

3. Theme: this method is most useful when examining different perspectives on a topic, as it helps the reader to understand the different “camps” of researchers.

Example: literature review examining common traits and behaviors associated with creativity

4. Methodology: this method is most useful when the purpose of the review is to derive a new methodology for examining the same problem, to justify the use of a particular methodology, or to discredit certain articles/studies based on methodology (focuses on how the research is conducted as opposed to conclusions drawn).

Example: literature review examining/comparing the methodology of a variety of studies that investigate ideal body mass index for athletes, or examining different methodologies used to investigate the most cost-effective retirement system for career military personnel

The literature review will typically conclude by summarizing the main perspectives discussed in the body. It might present some ideas for future research. If the literature review is part of a longer research paper, the conclusion might include a transition into the next segment of the paper.

CSG 6.2.5 Sample Literature Reviews

The following presents a few literature review excerpts. Note: many of these literature reviews have been truncated in the interest of space.

Literature reviews may note areas in which authors are in agreement.

Recent studies have focused on creativity as a collective endeavor. Annalisa Sannino and Viv Ellis recognize that “creativity has been primarily conceptualized as the quality of an innovative individual or as a novel outcome of individual action . . . such a view disregards the collective processes of creation, the learning involved in those processes, and their foundational role in cultivating creative minds as well as in producing creative outcomes of societal relevance.” Cathrine Hasse echoes this argument, claiming that creativity is not an individual art and is largely based on an individual’s community. For instance, learners will tend to develop the type of creativity that is supported and encouraged by the institution with which they associate.

Literature reviews may note areas in which authors disagree.

According to Lisa C. Yamagata-Lynch, Lev Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory of cognitive development can be seen as rebelling against behaviorist learning models that focus specifically on quantifiable, observable behaviors. According to B. F. Skinner, a prominent behaviorist, “Behavior is shaped and maintained by its consequences;” thus, teaching methods focus on positive and negative reinforcement in order to yield a particular behavioral response. By rejecting the idea of this direct stimulus response relationship in learning, Vygotsky attempted to formulate a model that would take into account individuals’ motivations for learning, as well as cultural and environmental factors that might influence learning.

Literature reviews may highlight debates among researchers.

There are several aspects of creativity that are still debated. For instance, scholars are divided as to what degree “ethicality” and benevolence should be considered a feature of creativity. In her book The Creative Mind, Margaret A. Boden views creativity as something that can be self-serving; further, Paul Gill et al. investigated an even darker side of creativity when they developed a conceptual framework to investigate creativity and innovation within terrorist organizations. Keith James and Damon Drown have furthered the concept of malevolent creativity in order to shed light on how societies might counter or disrupt terrorist organizations. Though the field has increasingly acknowledged the possibility of using creativity for dishonorable purposes, scholars remain divided as to whether creative products only include those that are beneficial to society.

Literature reviews may be used to highlight gaps in research.

Boko Haram in Cameroon in general—and the recruitment of Boko Haram combatants from Cameroon in particular—has not attracted the attention of many authors, despite the rich literature that exists on Boko Haram in Nigeria. However, a few publications have been of interest in the preparation of this research paper. An article by Corentin Cohen on political instability in Lake Chad gives a general picture of Cameroon’s population and the old criminal habits of the people in the area where Boko Haram has been dominating sociopolitical life. Christian Seignobos, who writes on the innovation of war in the Mandara Mountains, highlights the changes in tactics and techniques used by Boko Haram both in Cameroon and Nigeria where the Mandara Mountains stretch. His major concern is the change in logistics and tactics over time. Writing on the operational activities in the fight against Boko Haram, Aziz Salatou investigates the lack of a coordinated action of Cameroonian forces against Boko Haram in his article “Cacophony au Front” (Cacophony on the Front). Perhaps the best synopsis of the subject is a November 2016 article published by the International Crisis Group, which estimates that there are 3,500–4,000 Cameroonians currently serving as combatants for Boko Haram. Although these authors have been elaborate in their analysis, they have failed to sufficiently address the crucial problem of the recruitment of terrorists. The space dedicated to recruitment of insurgents does not permit them to answer the following questions: who, where, why, how, and with whom was the recruitment of insurgents done in Cameroon. It is such a gap in academic research that this paper sets out to fill.

A literature review may trace the roots and influences of a theory.

Sun Tzu, an ancient Chinese philosopher of war, heavily influenced John R. Boyd’s concept of maneuver conflict with the ideas contained in his classic work The Art of War. Along with an explicit focus on the mind of the enemy, Sun Tzu’s thoughts throughout The Art of War emphasize the importance of concepts Boyd distinctively considered central, such as variety, harmony, rapidity, and initiative. Sun Tzu’s concepts of cheng and ch’i are essential to creating uncertainty and confusion in the mind of the adversary, by maximizing variety and harmony to seize the initiative. Sun Tzu defines cheng as the expected and ch’i as the unexpected. The Art of War uses these concepts in tandem to create an advantageous situation, ideally allowing friendly forces to exploit an enemy’s weakness by showing the enemy the expected and then executing the unexpected.

Boyd also took an interest in the concepts auftragstaktik, schwerpunkt, and nebenpunkt, which are complementary to Sun Tzu’s concepts of cheng and ch’i. Auftragstaktik is commonly interpreted as mission-type orders. Although Boyd uses the term only once in the brief, “Patterns of Conflict,” he clearly defines and stresses the concept’s importance. When utilizing mission-type orders, commanders provide clear guidance of what they want accomplished, but they allow subordinates to determine how to accomplish their intent. In turn, each subordinate is obliged to conduct actions to achieve the commander’s intent. This arrangement allows for the subordinate to exercise initiative in execution, which results in variety based on the subordinate’s individual decisions, increased rapidity, and harmony of action toward a single commander’s intent. However, Boyd argues that the harmony only extends between the specific commander and subordinates.

Literature reviews might summarize attitudes about a particular event.

While many studies of the Battle of Agincourt exist, most of them reach a similar conclusion: leadership and discipline on the part of King Henry V and his English army allowed for a smaller force to win against a larger French force while in France. From these tenets of leadership and discipline, four qualities are germane to this analysis: control of the battlefield, tactical employment of forces, target selection and discrimination, and the integration of protection and fire support. While these four qualities do not explain England’s victory at Agincourt completely, they are the most applicable concepts for the study of potential manned and unmanned teaming (MUM-T) in future warfare and are thus the most pertinent to this analysis.

Literature reviews might criticize aspects of methodology.

In her article “Enhancing Creativity in Older Adults,” Kathy Goff discusses the shortcomings of the research on creativity and older adults, but neglects current research on creativity in adulthood. While the author asserts that little is known about creativity in adulthood, the publications used to support her argument date back nearly 10 years. She also fails to fully address two older, relevant studies that are often considered foundational to the research on creativity development in adults: Marge Engleman’s six-week study of older adult women, which includes qualitative data to support the possibility of improved creativity in old age, and Karol Sylcox’s 1983 study, which substantiates Engleman’s findings. Furthermore, Goff’s research methodology is of concern, as she does not discuss the validity or reliability of the tools she used to measure the development of creativity in her experimental group.

Literature reviews may highlight key themes in the research.

When reviewing teaching methods that tend to facilitate stronger decision-making skills, a few themes emerged. First, narrative and storytelling can improve individuals’ decision-making skills by helping learners to broaden their frame of reference, which may be akin to “artificially” developing experience. Further, decision-making is improved by strengthening pattern recognition capabilities. Finally, decision-making is improved through mental practice. Because many of these qualities are inherent in case studies, the majority of this section will focus on this particular teaching technique and how it might be used to improve decision-making skills. The paper will also address mental simulations, which help to improve “mental practice.”

A literature review may be used to show where you fit into the critical conversation.

On 17 December 2010, Tunisian municipal police in the town of Sidi Bouzid assaulted 26-year-old fruit vendor Mohamed Bouazizi and confiscated his fruit and electronic scale. He and his family immediately logged an unsuccessful appeal to the municipal authorities for the return of his property. In reaction, Bouazizi “doused himself with paint thinner” and set himself on fire in front of the local governorate building just one hour after the assault. The nationwide antigovernment riots and demonstrations that soon followed caused Tunisia’s autocratic president, Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali, to flee Tunisia on 14 January 2011 after holding power for more than twenty-eight years. Most critics agree that Bouazizi’s death and the subsequent overthrow of the Tunisian government signaled the beginning of the Arab Spring. Large protests soon erupted across the Middle East. Autocratic presidents also stepped down in Yemen and Egypt, while civil wars began in Libya and Syria. Some observers in the West soon dubbed these “Twitter Revolutions,” crediting “New Media” tools—especially social media like Facebook, Twitter, and websites like WikiLeaks—with creating the revolutions.

On 13 January 2011, The Atlantic’s Andrew Sullivan proposed that the unrest in Tunisia “might actually represent a Twitter revolution as has been previously promised in Moldova and in Iran.” In July 2011, critic Judy Bacharach stated that a WikiLeaks document about Ben Ali and his family’s corruption provided “the rationale for the revolution,” which “was devoured by millions of Tunisians.” Despite these commonly held theories, after further examination, it is apparent that Western observers overestimated the effect and importance of social media during the Arab Spring. While the internet and social media were important tools used by urban youth, the internet and platforms like Facebook and Twitter lacked the required saturation; other more traditional forms of communication including television and simple word of mouth were more prevalent and played a more significant role.

A literature review may highlight exemplary studies or works on a topic.

Daniel Kahneman is perhaps one of the most widely cited researchers on the topic of decision-making. In his Nobel Prize-winning text Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman strives to understand how decisions are made in order to improve organizational decision-making. Kahneman discusses decision-making primarily in terms of what he calls “System 1” and “System 2” thinking. The System 1 thinking he describes in the text refers primarily to what some of us might think of as “fast” thinking while characterizing System 2 thinking as slower and more deliberate. Kahneman is wary of the benefits of intuitive thinking, as he sees System 1 as fundamentally flawed. He claims that most people do not use rational decision-making practices; instead, they rely on what he terms “decision bias.”

Gary Klein, another frequently cited author on the topic of decision-making, is more optimistic about the benefits of intuitive thinking and believes most experts use some form of intuitive thinking when making decisions under pressure. In one of his most well-known studies, Klein observes how a group of experienced firefighters make decisions. During this experiment, he noticed the firefighters did not weigh options in order to select the best decision, as many of the researchers conducting the study (including Klein) had hypothesized. Rather, the firefighters selected the first feasible course of action. Klein has termed this theory on decision-making the recognition-primed decision (RPD) model. The premise of this model is as follows: “Proficient decision makers are able to use their experience to recognize a situation as familiar, which gives them a sense of what goals are feasible, what cues are important, what to expect next and what actions are typical in the moment.” Klein further posits that the key to successful decision-making in time-constrained environments is pattern recognition, not analysis.

CSG 6.3 Evaluating Your Sources

Regardless of whether you are required to write a formal literature review, you will still need to evaluate your sources in any paper you write that requires outside research. When you review a source, it is important to remember you are not only reading to make sure it suits your purpose but you are also evaluating the author’s credibility and logic. There are four areas to consider when you evaluate a source: reliability, credibility, objectivity, and neutrality. All of your sources should be reliable and credible. Some of your sources may not be completely objective or neutral, and that is okay: you will use your critical reading skills to discern how to use those sources appropriately in your argument.

Reliability determines the extent to which a source’s claims and presentation of the facts are consistent and verifiable. If someone were to tell you her counterinsurgency strategy is effective, reliability would be lowered if you were to find out a group of commanders had employed her strategy in Vietnam with limited success. The source’s reliability would increase if other data (e.g., personal letters, orders, photographic evidence, and personal interviews) validated the individual’s theory and demonstrated that the strategy she proposed had been consistently effective.

Credibility directly relates to your capacity to believe a source or a research conclusion. Reliability influences a source’s credibility. For instance, if the unsuccessful theorist in the example above were to develop a new counterinsurgency theory, she would have little credibility because her previous claims were false; hence, they were not reliable. Likewise, individuals’ positions and experience may affect their credibility. If someone were to tell you her theory about professional military education (PME) is effective, credibility would be lowered if you were to find out that individual had never taught at a PME institution or had never been exposed to military culture before. Credibility would increase if that individual could show you statistics proving the effectiveness of her theory on a targeted group of PME students.

Objectivity refers to an author’s ability to present ideas that are not colored by bias, individual interpretation, or personal feelings and/or opinions. Additionally, it refers to an author’s ability to present several sides of an issue (i.e., the authors must address counterarguments). For instance, if one were to argue that the current president is unable to meet the economic policy needs of the nation, the author would need to examine the issue using a variety of sources written by both individuals who are politically aligned with the president and those who oppose his policies. Objectivity would increase if the author of the source could state the argument simply based on facts, statistics, and/or logical arguments gleaned from accurate statistics. The use of neutral sources may help to bolster objectivity. You can often tell when a source is not objective by examining the type of language and tone the author uses. Texts that use hostile language when referring to a particular group of individuals or a particular philosophy are not objective.

Neutrality refers to the degree to which the author has an interest—whether social, political, or economic—in the subject at hand. For instance, if a writer were to argue the United States military needs to pull all troops out of a certain location, and you find out this individual’s sibling was set to embark on a dangerous mission to that location, the neutrality of this text might be questionable. Likewise, if someone were to argue that the current president cannot meet the economic policy needs of the nation, neutrality would be compromised if you were to find out that individual was a candidate from an opposing party in the upcoming presidential election. Neutrality would increase if the individual was not partial to either political party and was simply a subject matter expert in American economic policy. You will often want to briefly research a text’s author and his or her affiliations before you begin reading, as this process may help you to determine to what degree the text may be considered neutral. However, few texts are genuinely neutral, as most authors are personally invested in their work and the particular truth they wish to convey, even if their presentation of the facts is objective. Suggestions for strategies you can use to evaluate sources are found in table 7.

Table 7. Determining the relevance and veracity of a source

|

|

Determine relevance

|

Evaluate veracity

|

|

Book

|

1. Use the index to look up words that are related to your topic.

2. Review the table of contents to determine whether smaller sections within the book pertain to your topic.

3. Read the opening and closing paragraphs of relevant chapters; skim headings.

4. Determine whether the book is too specialized or not specialized enough.

5. Check the publication date. If significant advances have been made in the field since the book’s publication, the text may no longer be relevant.

|

1. Keep the author’s style and approach in mind. Is the book scholarly enough to be considered credible?

2. Do the ideas seem biased?

3. Read the preface: What is the author’s motivation for writing the book? How may their affiliations and goals affect their interpretation of the facts?

|

|

Journal article

|

1. Look for an abstract or statement of purpose at the beginning of the article.

2. Read the last few paragraphs, as these often will provide a summary or conclusion of the article’s main points.

|

1. Is the publication peer reviewed?

2. Who publishes the journal? Is it an organization with a particular agenda?

3. Are the authors scholars, journalists, politicians, or professionals?

4. Are the conclusions drawn from original research?

|

|

Newspaper article

|

1. Focus on the headline and the opening paragraph.

2. Skim the headings and look at visuals that may indicate the article’s focus.

|

1. Does the newspaper have a nationally recognized reputation?

2. What type of newspaper article are you reading? Editorial opinion pieces may have a different level of bias than more factual pieces, for example.

|

|

Website

|

1. Look at the home page. Is the information relevant to your research question?

2. Find out when the website was last updated. Is the information current enough for your purpose?

3. What are the motives/interests of the sponsor/organization that maintains the website?

|

1. What is the purpose of the website? Is it trying to sell a particular product/idea?

2. Check the name and credentials of the author or webmaster. If you have trouble finding the author’s name or information about the sponsors, be wary of the information.

|

CSG 6.4 Varying (Triangulating) Your Sources

As you think about evaluating sources and checking for potential bias, keep in mind the more sources and different types of analysis you can use to support your thesis, the more credibility your work will have. This process of collecting multiple sources of data that come together to support a particular point is commonly known as triangulation. Triangulation adds to the academic rigor of your work because it demonstrates to the reader that the conclusions you have drawn are not a result of biased observation. The following is an example of how you can use triangulation of data to support your thesis. Consider the thesis statement below.

The surge of American troops, coupled with local and militia uprisings, formed the catalyst for the Iraqi Army’s (IA) progress in critical areas, such as logistics, personnel recruitment and retention, and pay administration, which contributed to building the confidence and performance of the IA in 2007.

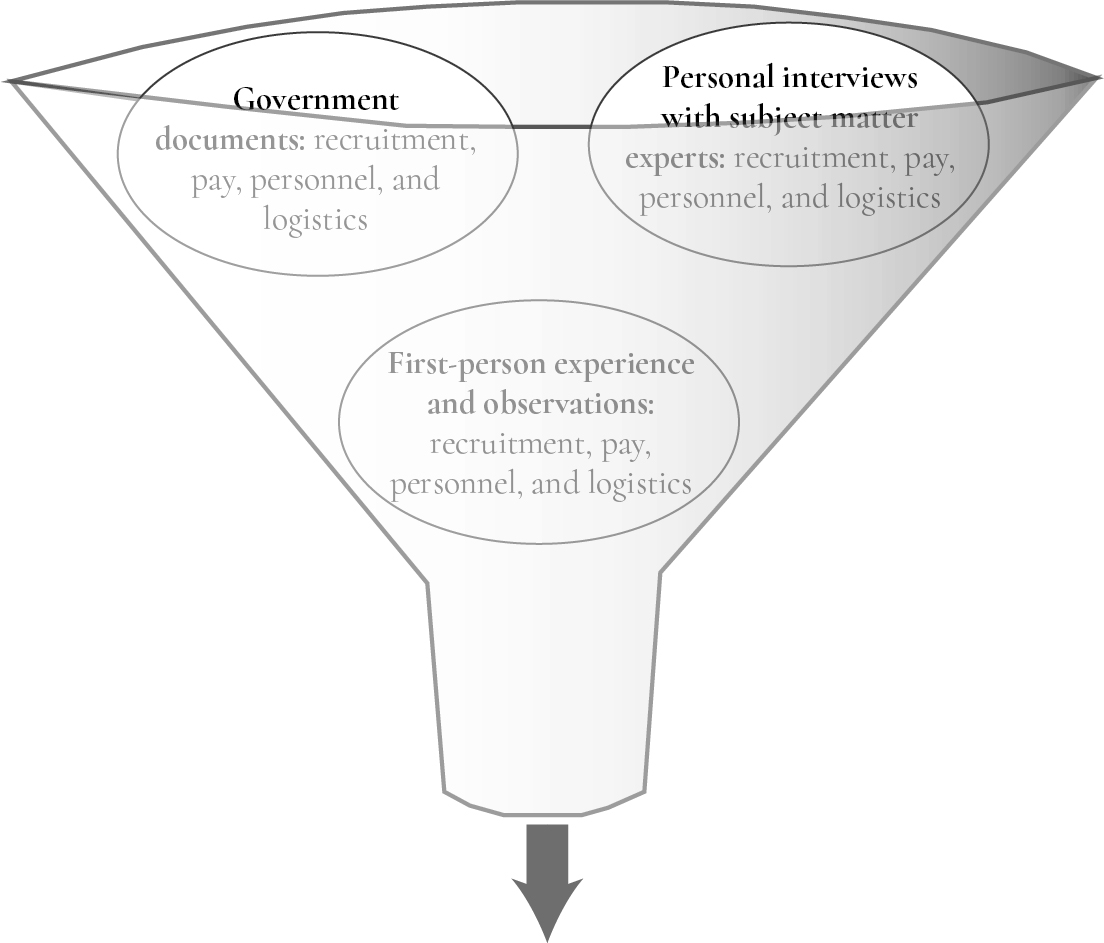

In this study, the researcher used multiple sources to highlight the patterns and trends that resulted from the troop surge in Iraq. He traced these trends—logistics, recruitment, personnel, and pay—in all of the sources he consulted. Figure 30 is a visual representation of how the researcher triangulated the data to support his central claim.

Figure 30. Triangulation of data to support a claim

Whether you use an historical approach or an experimental approach to collect data, you must learn to manage the data. In this instance, you need to manage means to archive, store, and/or arrange the data into a system so the data is easy to retrieve. Some of the data may include articles, book chapters, or published interviews. You may collect your own primary data by using interviews and surveys of your own. Note: before interviewing or surveying human subjects, you will want to read your institution’s rules on conducting original research.

CSG 6.5 Primary Research

As you conduct your research, you may find a need to gather your own primary data. This can involve interviewing experts, holding focus groups, observing activities in the field, or surveying a representative group of individuals who have shared experience or knowledge that might be relevant to your research. You may also want to access secondary data sets that have already gathered such data but may contain private identifiable information or may not be publicly available. Primary research allows you to collect information directly connected to your research topic from a specialized audience.

While offering many benefits, these research activities do require additional preparation, and planning. If your research:

• meets the federal definition of human subject research, approval by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) is required.

• involves gathering data from ten or more individuals, approval by the Survey Program is required.

If you are considering a research plan involving gathering information from/about people (e.g., interviews, focus groups, surveys, or questionnaires) or access to private or identifiable data (e.g., personnel data), reach out to MCU’s director of research and IRB vice chair, Dr. Kerry Fosher at kerry.fosher@usmcu.edu early in the research design process.

According to Marine Corps policy, researchers cannot make determinations about the applicability of research policy on their own—review is required.

Additional Information about research policies, review processes, and opportunities for data sharing is available on MCU’s Research and Sponsored Projects Portal.

CSG 6.5.1 Deciding to Conduct Primary Research

With purposeful design, primary source data can provide unique insights into a research topic. Students considering whether to invest time and resources into primary source research should first determine whether the information they propose to gather is available via secondary sources. If it is not, consider the following questions as you consider whether and how to pursue primary source research:

1. What sort of information do you want to find? Try to articulate the purpose of your interview or survey in a single sentence.

2. Are you seeking to identify numerical trends and/or measure perceptions (quantitative) or to delve more deeply into meaning and experiences (qualitative)?

3. How might this information connect with your research question(s)/thesis statement?

4. What types of analyses will you need to conduct? What skills or technical resources would be needed to support your project? Are they readily available?

5. Whom will you interview or survey? Which specific group(s) of people will have the knowledge or experience that is relevant to your interests? Do you have access to this population?

Many students also consider the usability of their results in this cost-benefit analysis—will your research connect to practice? For this reason, some students seek out a sponsor through professional networking or the Marine Corps and Joint Professional Military Education (JPME) Prospective Research Topic Database (PRTD, CAC enable site). Connecting with these practitioners in the field presents another avenue for discovering existing data or literature that you can leverage in your research.

Considering these questions will give you insights into your research design and approach, as well as into the feasibility of your primary research. The complexity of the research question and proposed analyses, availability of resources for those analyses, and the size and location(s) of the target population are all factors that can constrain or prolong research design, data gathering, and analysis. These considerations will also impact whether your research will be subject to the reviews described above.

CSG 6.5.2 IRB and Survey Program Review Criteria

IRB: an IRB applicability review involves completing a short form describing your research plans. The IRB determines whether the proposed project meets the federal definitions of human subject and research:

Researchers are informed of the IRB’s applicability determination by the MCU IRB vice chair and advised if further action is necessary. If the determination is that the project is not human subjects research, no further IRB review is required. If it is human subjects research, the researcher completes a full research protocol, which is reviewed by the IRB.

|

Human subject

|

Research

|

|

A living individual about whom an investigator conducting research obtains:

data through intervention or interaction with the individual or

identifiable private information.

|

A systematic investigation, including research development, testing, and evaluation, designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge

|

Survey Program: regardless of the human subjects research determination, if the research involves a survey, focus groups, or interviews with more than nine people, a Headquarters Marine Corps Survey Program review is required. If the proposed participants are from another Service, the survey office will connect the researcher to the relevant Service point of contact. Cross-component information collection involving more than one Service requires a higher-level survey order review. Research involving members of the public, to include retirees and Department of Defense (DOD) contractors, or that addresses topics specified in MARADMIN 314/21 may require a six-to nine-month OMB review. There are exceptions to these requirements. For more information, contact MCU’s director of research, Dr. Kerry Fosher at kerry.fosher@usmcu.edu, early in the research design process.

CSG 6.5.3 Timeline for IRB and Survey Program Reviews

NOTE: in most cases, planning and implementing primary research is manageable within the school year. However, because review timelines vary based on project details, researcher should begin the process 60–90 days before they plan to recruit participants or request data.

IRB: applicability reviews—in AY22, requests for applicability reviews that followed the guidelines on MCU’s Research and Sponsored Projects portal typically were processed in less than one week.

Full protocols (if required): the timeline for approval of a full research protocol varies based on the following considerations:

• The level and type of risk the research creates for participants;

• Whether the research qualifies for an expedited or exempt review category; and

• The level of review required. A higher-level Human Research Protection Program (HRPP) review can only occur following completion of the survey order review process and is required when proposed participants include the following:

– Individuals from more than one Service (U.S. Navy and Marine Corps are treated as one Service);

– International participants; or

– General public, including retirees and DOD contractors.

Completeness of information and audience awareness is critical to a speedy review. Follow the guidelines you receive from the director of research and, if in doubt, ask for help.

Students often underestimate the time involved in completing an IRB protocol, which requires thorough descriptions of the research plan and tools. A full protocol requires you to describe the background and objectives of your research, as well as details of the methodology (subjects/target audience, data gathering and analysis plan, data access and security) and your final data collection instrument (survey questions, interview protocol, etc.). In other words, you must present a developed research proposal.

Survey program: survey program reviews vary considerably based on the specific details of the project. During AY22, survey program review timelines for simple projects submitted by students averaged two weeks. Complex projects and projects submitted by faculty and staff took considerably longer.

Whether you are receiving access to data, coordinating interview times, or building a survey in an approved survey platform, the set-up and coordination of your research after IRB and Headquarters Marine Corps Survey Office reviews will add additional time before you are able to collect data. Students should also budget sufficient time to analyze and incorporate data into their final project in accordance with academic deadlines.

For access to current forms and more information, visit MCU’s Research and Sponsored Projects Portal.

CSG 6.5.4 Ethical Research

Regardless of whether a project is considered human subjects research, there are professional expectations and ethical best practices that should be reflected in research design, administration, and analysis. All research activities should adhere to the ethical practices of informed consent (i.e., ensuring participants understand how their information will be used and the risks involved), voluntary and fair participant selection, and cognizance of minimizing harm while maximizing benefits to participants. For more information, contact MCU’s director of research, Dr. Kerry Fosher, at kerry.fosher@usmcu.edu.

CSG 6.5.5 Designing Primary Research and Data-Gathering Tools

Design of your research instruments, such as surveys or interview questions, is critical to getting the right information to inform your study. The remaining sections provide some strategies and tips for designing, testing, and planning surveys and interviews.

For students with specialized research design needs, MCU will make an effort to link them to internal and external Marine Corps scholars/scientists who can assist them on an individual basis. This support is provided through a network of scholars/scientists in the LCSC; Academic Affairs; Institutional Research, Assessment and Planning (IRAP); and the schoolhouses. For more information, contact MCU_ResearchResources@usmcu.edu.

CSG 6.5.6 Survey and Interview Questions

When you conduct a survey or prepare for an interview, you will want to be sure your questions are clear, specific, and unbiased. You want to be sure your questions will actually yield the information you are seeking.

Open-ended questions and closed-ended questions are two basic types of questions you can use to gather data. Closed-ended questions require respondents to select their answer from a finite number of responses, while open-ended questions allow respondents to offer original information that best answers the question. Below are examples of the two question types.

Closed-ended question: Did the ethics training you received predeployment prepare you adequately to make difficult decisions in combat situations? (Yes/No)

Open-ended question: In what ways, if any, could the Marine Corps improve its predeployment ethics training to better prepare Marines for making difficult decisions in combat situations?

As you construct an interview or a survey instrument, your sample size will drive the type of questions you choose to include. For example, if you are interviewing a single individual, it is a good idea to have a list of open-ended questions designed to allow that individual free range in response, thus providing you with rich information. In an interview situation, you can ask follow-up questions to get more information from your subject. However, if you are planning to survey a number of people, closed-ended questions make it easier to tabulate and interpret responses. These questions tend to yield more consistent data, making the responses easier to collect and interpret. Closed-ended questions are less time-consuming for respondents, thus making it more likely they will answer. However, closed-ended questions can be limiting, so you may have to create more questions to gather sufficient data. Open-ended questions, on the other hand, allow for freer, individualized responses. They are sometimes difficult to interpret because they tend to evoke original responses that vary from one another.

When constructing interview and survey questions, you will want to avoid using leading questions, double-barreled questions, and ambiguous quantifying words.

Leading questions contain some of the interviewer’s own biases or views. See the following example:

It seems to me that the pushing down of intelligence assets (i.e., company intelligence cell) is a natural evolution paralleling the changing character of warfare. What are your thoughts?

This interviewer is first telling you his or her own perceptions and does not orient the question to what you, the responder, perceive to be the case. A better way to solicit this information might be as follows:

In your opinion, what kind of effect would providing a battalion-level intelligence cell have on the battalion?

Double-barreled questions often have a question embedded within a question; they ask two questions at once. Frequently, the words and and or may signal a double-barreled question. An example would be, “Do you think military officers should receive culture training and language training?” These questions should be listed as two separate items because they contain two different ideas. A survey participant may think military officers should receive language training but not culture training or vice versa. A suggested revision would clarify the ambiguity with one of the options listed below.

1. Should military officers receive both culture training AND language training?

2. Should military officers receive culture training? Should military officers receive language training?

Ambiguous quantifying words are vague ways of describing something and can confuse meaning. See the example below.

How well did your organic intelligence capability support planning?

In the above example, the word “well” is a bit vague and leaves too much room for interpretation. When asking survey participants to evaluate a particular person, process, or idea, consider using a Likert scale instead of using vague descriptors. A suggested rewrite might be as follows:

On a scale of 1 to 5—with 1 representing “not at all” and 5 representing “extensively”—how would you describe the extent to which your organic intelligence capability supported planning?

CSG 6.5.7 Pilot Testing

If time allows, you may want to pilot test your survey before administering it to your sample population. To pilot test your interview/survey questions, try having a person who matches the demographic of the sample group answer your questions. You should not use the responses you obtain from this person in your actual study; however, the responses will give you some insight into whether or not the questions you have developed are effective.

By asking the questions, you may find out terminology you thought was familiar and easily understood is not familiar to the people within your sample. The questions you ask interviewees could be interpreted in multiple ways, or the questions you ask may not yield the answers you are seeking. Once you have conducted the pilot test, you should know whether or not some of the questions need tweaking.

CSG 6.5.8 Conducting Surveys

Once you have designed your survey instrument, you should consider how it will be administered. Will you administer the survey yourself, will you email the survey to potential respondents, or will you enlist others to assist you in administering the survey? While it may be efficient to administer the survey yourself to a group of people who are all in a room at the same time, this situation reduces anonymity and may affect the way in which individuals respond to the survey. If you email the survey to potential respondents via a link (e.g., Survey Monkey or some other survey tool) you risk not having everyone finish the survey, even if they had agreed to complete it ahead of time. Allow yourself plenty of time to collect, tally, and interpret the data on your returned surveys.

CSG 6.5.9 Conducting Interviews

Similar to conducting surveys, you need to make sure the people you are interviewing represent the group you are studying. If an individual is an exception to the rule, you need to indicate this in your field notes. The best place to conduct an interview is in a quiet environment, away from the individual’s office, and without personal or electronic interruptions. In addition, make sure you have permission to record the person’s answers. Let the person know you will maintain confidentiality and anonymity, if he or she desires. Furthermore, tell the interviewee you will send him or her a copy of your completed study. This arrangement enhances your credibility with the interviewee and puts him or her at ease.

It is important to allow interviewees to express their thoughts in their own words and for you to record their responses verbatim. You can always ask a clarifying or follow-up question if interviewees do not give you enough information, but do not show approval or agreement with their responses. Instead, monitor your nonverbal gestures. Finally, if you are conducting a focus group, make sure to take group dynamics into account. Several factors affect group dynamics including interviewees’ ranks, positions in the organization, experiences with the topic, personal feelings about the topic, and homogeneity.

CSG 6.6 Organizing Your Research Data

As you collect your research data, you will need to develop a system to keep your information organized and accessible to you for when you are ready to write. Most researchers find maintaining a working bibliography can help them organize their research.

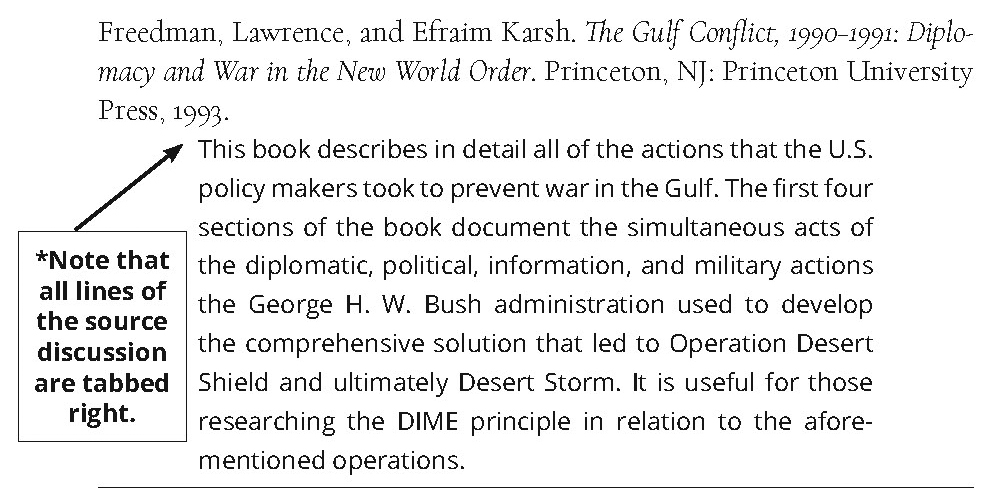

As you select sources to use for your project—for your background reading, for your literature review, and for your argument—compile a working bibliography. Write down the bibliographic information about each source, and then annotate each entry. That is, write a paragraph with key information about the source you have cited. The annotation should contain a brief summary of the information in the source as well as how that information relates to your research question or your thesis statement. Your annotation could contain a key quote or your own evaluation of bias in the source. Finally, you will want to annotate how each source relates to the other sources in your bibliography. Figure 31 is a brief example of an annotated bibliography entry.

Figure 31. Annotated bibliography entry example

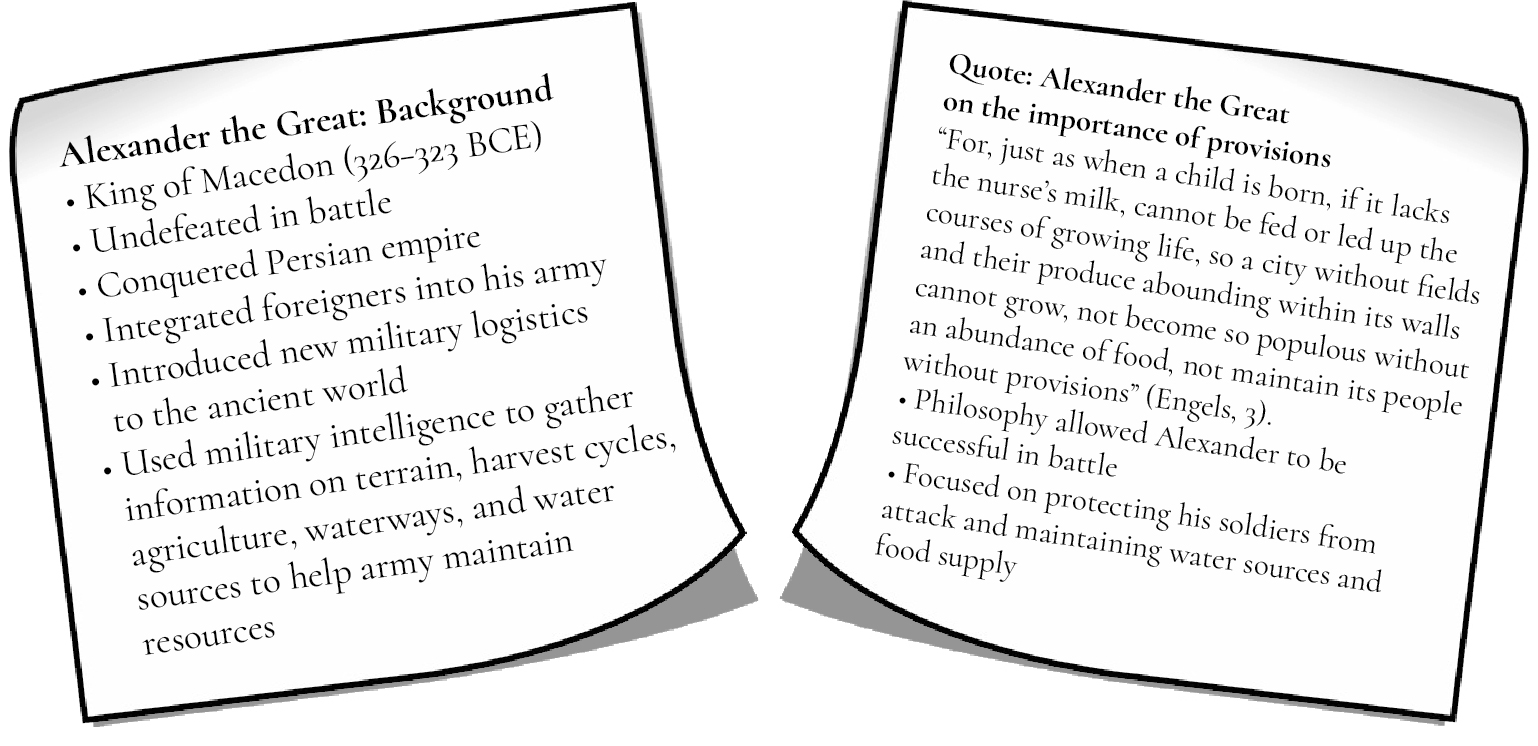

As you begin to take more detailed notes about your sources, you should develop a system that works for you. Many of your sources will be in digital form, so you should store files of those sources for easy retrieval. As you review and read your sources carefully, you may use a note-taking tool to highlight and make notes directly on your digital copies. Researchers use many different note-taking methods. If you are unsure of where to start, you may find a traditional note card approach to be helpful when you are working with multiple sources. You can group note cards or post-it notes according to topic and source. Assigning source and topic numbers will help you to organize your information. You may use different colored note cards to represent the various topics you intend to discuss in your paper. Assigning topics to a particular color note will not only help you to organize your information but will also help you to lay out your thoughts when you begin to write your paper.

A more contemporary approach to the note card strategy is to outline your ideas on PowerPoint slides. You may devote each slide to a particular topic or to a particular portion of your paper. Make sure to only include one topic and one source per note card or slide. This approach will make it easier to organize your ideas when you have to write your paper. Additionally, you will want to indicate whether the information on the note card or slide is a paraphrase or a direct quotation. If the quotation is long or complex, you may want to include your own paraphrase to simplify the information. Another approach is to use a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet to break down your research data into searchable cells. You can organize this spreadsheet by topic, author, page numbers, or any other organizational structure that works best for you.

It is important to take notes carefully. Be sure you use your own language to summarize ideas. While it is very easy to use the language in the source for your notes, that can lead to plagiarism. Some researchers prefer to take notes without looking at the source so as to avoid unintentional plagiarism. Carefully distinguish your own ideas from quoted or paraphrased material. This distinction will help you to avoid plagiarism, especially if you are going to take notes electronically. Likewise, if you are going to cut and paste information from a digital source, make sure you immediately differentiate the quote from the rest of the text. You will want to place all directly quoted material in quotation marks, and you may even want to bold or highlight this text to distinguish it from the original ideas and analysis you include in your notes. It is so easy to paste in text from a digital source that students sometimes plagiarize unintentionally as a result. You can find more information about plagiarism in chapter 8. Figure 32 illustrates a few sample post-it notes.

Figure 32. Post-it note examples

CSG 6.7 Connecting Your Research Data to Your Research Question

When you develop your research question, you may begin to form a hypothesis—that is, you will make an educated guess about the conclusions you will draw from your research. At this point, after taking notes on the many sources and pieces of data you have collected, you may ask: What if my assumptions are wrong? What if my data does not support my assumptions? Will this mean all of my research and hard work has been in vain?

The advantage of the research question is that the rigor and success of a study has nothing to do with whether the conclusions you reach support your original hypothesis. Instead, the success of a research project depends on your ability to use your data in an effective, logical manner. For instance, a researcher may set out to demonstrate that commercial travel to the moon is economically sustainable; however, after conducting research, he or she may find data that disproves this hypothesis. As long as the researcher can supply adequate information to support the idea that moon travel is not economically sustainable, the study will still have validity. This constant evaluation and reevaluation of assumptions is part of the cyclical nature of research.

Additionally, remember you started out with a research question that you may answer in more than one way. If your data does not support your initial hypothesis, you can draft a new hypothesis—which is based on the data you have collected—to answer the research question.

Once you have conducted your preliminary literature review, you can further narrow your topic. Keeping in mind the main critical perspectives in the field, the research that has already been conducted, and the data you have collected, you will need to go back and review your research question. Is the question still relevant? Has another researcher already answered the question? Is the question too broad? You should revise your question on the basis of your research and then begin to formulate the answer to that question in what is commonly called a working thesis statement, which will be discussed in chapter 7.

This chapter provided a general overview of the research process, but the information is by no means exhaustive. We have only just scratched the surface of what can be an intimidating topic for many students. If the last two chapters have left you wanting to know more about the research process, below is a bibliography of sources you might consider consulting:

Booth, Wayne C., Gregory G. Colomb, Joseph M. Williams, Joseph Bizup, and William T. Fitzgerald. The Craft of Research. 4th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016.

Creswell, John W., and J. David Creswell. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 5th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2018.

Leedy, Paul D., and Jeanne Ellis Ormrod. Practical Research: Planning and Design. 8th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2004.

Swales, John M., and Christine B. Feak. Academic Writing for Graduate Students: Essential Tasks and Skills. 3d ed. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2012.

Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 2d ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1994.